Some days, I wonder where the financial publishing and blog world would be if Warren Buffett was not the universally renowned icon that he has become. If you scan a listing of the most prolific sources of financial feature pieces, you are almost guaranteed to discover that an outsized number of them refer somewhere in the title (or subtitle) to Buffett. I confess that I, myself, could be convicted in a court of law on that charge – so I am quite grateful that writing about the “Oracle of Omaha” is not illegal!

One of the reasons that Buffett commands such attention is that he offers a commentator or analyst at least 54 years of trading history! That, in and of itself, is a rarity. But more to the point, Buffett is appealing, articulate, affable, and never afraid to speak his mind – especially when he is expressing a minority opinion (such as in 2009, when he said the stock market had become irresistibly appealing).

As we know, Buffett has become famous because his investment record is fabulous! But the average investor has never taken the time to learn Mr. Buffett’s story from the beginning! That is unfortunate, because his story is rich with amazing anecdotes!

Today, I want to tell you the story of the “Twelve and One-half Cents” that became Buffett’s biggest investment mistake – causing him an “Opportunity Cost”[1] of approximately $4.44 billion per year (on average) between 1964 and 2010!

OK, OK… I know that is extremely hard to believe! We don’t normally think of the “Oracle” as being fallible… especially in the world of investments! But I did not make this story up — it was told by Mr. Buffett himself in 2010. What I offer below is my recounting (with background material added so you can gain a more complete perspective) of what Buffett calls “the biggest investment he has ever made”!

The story starts in 1962, when 32-year old Warren Buffett became intrigued by a persistent price pattern in the stock of a company that descended from an old-line 19th Century New England textile manufacturer – the Valley Falls Company (in Rhode Island) – founded by Oliver Chace (remember that name!). Ninety years after its founding[2], Valley Falls merged with a younger textile firm named the Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company (in Massachusetts) – becoming (of course) Berkshire Fine Spinning Associates! Finally, in 1955, the textile firm founded by an old New England seaman (China Trade), industrialist, and politician named Horatio Hathaway (the Hathaway Manufacturing Company) merged with Berkshire to become the Berkshire Hathaway Company!

To the left is an 1898 photo of a textile plant operated by Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company in Adams, MA.

To the left is an 1898 photo of a textile plant operated by Berkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company in Adams, MA.

It is not questioned by anyone (including Mr. Buffett) that the textile industry was (in the 1960’s) on a steady decline, a decline that first manifested itself after World War I. The industry struggled (along with the entire country) during the Great Depression. Then came World War II, which produced unparalleled demand for a wide range of US industrial products – driving manufacturing into overdrive. The war and its aftermath (which included the accelerated demand coming from hundreds of thousands of newly formed families that gave birth to the “Baby Boomer” generation) offered textile mills a bit of a “new birth”. In fact, at the time of that 1955 merger, Berkshire Hathaway boasted fifteen plants, approximately 12,000 employees, and more than $120 million in annual revenue.[3]

To the left is an October 2007 photo of one of the old textile mills run by Hathaway Manufacturing Company in New Bedford, MA.

To the left is an October 2007 photo of one of the old textile mills run by Hathaway Manufacturing Company in New Bedford, MA.

This was a crucial period in the development of what we now know as Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-A; BRK-B) – and it was crucial for a reason that no one living then could ever have guessed! The company had captured the close attention of a young (as yet unknown) Warren Buffett.

Between 1955 and 1960, Berkshire Hathaway shuttered seven of its fifteen plants – with the accompanying (and inevitable) sizable layoffs of workers. The ever-observant Buffett, trained by “value” expert Benjamin Graham regarding how to tear through corporate financial reports to find the most promising investments, discovered an intriguing pattern in Berkshire’s price action on the exchange! Whenever management announced a plant closing and layoffs, the stock always reacted the same way. As a consequence, given Buffett’s confidence in the “numbers” and Berkshire’s price action, Buffett started buying Berkshire Hathaway common shares in1962. In classic Graham-fashion, Buffett described the company’s stock as priced significantly below intrinsic value.

Here is where the story took another transformative turn. During 1963, Buffett (and his investing partners) became the company’s largest shareholder! Naturally, Buffett began taking a more direct interest in the management of the company. And there came “the rub”.

Seabury Stanton (see his photo to the far left) was from a long-time New England whaling family (his grandfather and father had been whaling captains). However, Seabury was strongly drawn toward the textile industry – attending the New Bedford Textile School and then moving on to none other than Harvard University. Upon his 1915 graduation, Stanton took a position at Hathaway Manufacturing Company. Forty years later (1955) when the final merger took place that created Berkshire Hathaway, Seabury Stanton was president. The problem was that Stanton was a died-in-the-wool “textile aficionado”, not (by any stretch) an adept “financial manager”! While Buffett was always[4] alert regarding the importance of maximizing one’s utilization of cash in profitable ways, Stanton’s only priority was plowing cash back into the textile business to keep it going – even (it must be emphasized) though the writing was on the wall by the 1960’s that decreasing cotton prices and increasing competition (home and abroad) made reinvesting all company cash into textile manufacturing a dead end street.

Seabury Stanton (see his photo to the far left) was from a long-time New England whaling family (his grandfather and father had been whaling captains). However, Seabury was strongly drawn toward the textile industry – attending the New Bedford Textile School and then moving on to none other than Harvard University. Upon his 1915 graduation, Stanton took a position at Hathaway Manufacturing Company. Forty years later (1955) when the final merger took place that created Berkshire Hathaway, Seabury Stanton was president. The problem was that Stanton was a died-in-the-wool “textile aficionado”, not (by any stretch) an adept “financial manager”! While Buffett was always[4] alert regarding the importance of maximizing one’s utilization of cash in profitable ways, Stanton’s only priority was plowing cash back into the textile business to keep it going – even (it must be emphasized) though the writing was on the wall by the 1960’s that decreasing cotton prices and increasing competition (home and abroad) made reinvesting all company cash into textile manufacturing a dead end street.

[To the left is a photo of young Warren Buffett teaching a college class in Omaha]

[To the left is a photo of young Warren Buffett teaching a college class in Omaha]

Therefore, the moment that the still young Warren Buffett stepped up to express his views to Berkshire’s management, he and Stanton interacted much like a piece of flint as it meets up with steel — sparks flew!! Buffett pushed for a more profit-focused utilization of company resources, while Stanton’s single-minded bent was preservation of mills and jobs… not to mention the preservation of his son’s legacy.[5]

Assessing his options, given Buffett’s over-sized ownership stake in Berkshire, Seabury Stanton decided in 1964 that he needed to buy out Buffett’s entire stake. Therefore,[6] Stanton presented Buffett with a verbal offer to buy all his shares at $11.50/share. Buffett accepted the verbal offer and awaited the written confirmation of the sale/purchase from Stanton.

Here comes the crux of this story! Can you guess what happened? The formal written offer specified that the purchase price Stanton would pay Buffett was $11.375/share (ie. $11 3/8). To say that Mr. Buffett was upset by this divergence from the verbal agreement would be an egregious understatement. A more accurate description of Mr. Buffett’s reaction would be “infuriated”! All those “sparks” that had been accumulating during the interactions between Stanton and Buffett suddenly burst into flames… producing an emotional energy within Buffett sufficient to drive him to buy up more shares of the company – even securing a good deal of those shares from Otis Stanton, the quite disaffected brother of Seabury![7]

[To the left is another early photo of Buffett feeding his daughter]

[To the left is another early photo of Buffett feeding his daughter]

Needless to say, by 1965, Buffett held a commanding interest in the company and ensured that he would be able to exercise necessary accountability within management by becoming Chair of the Executive Committee. He replaced Seabury Stanton with Ken Chace and said a very relieved “goodbye” to Jack Stanton. Interestingly, he granted Chace considerable independence to run the textile business as he saw best; in fact, Chace wrote the annual company letter until 1970, by which time Berkshire Hathaway had a much larger vision than just textiles due to the first stirrings of the Buffett “genius”.[8]

Let’s explore why Buffett has referred to the decision not to sell to Stanton his biggest investment mistake. There are many ways to assess this question, so let’s just consider the possibilities, point-by-point:

1) At first, not selling wasn’t such a bad choice. Soon after he took control of Berkshire, the shares he had purchased for an average price of $15/share were valued at approximately $18/share. In addition, the company was considerably leaner and more efficient than in 1955, when it had fifteen mills and 12,000 employees!

2) However, Buffett realized that, at its core, the old school U.S. textile business was in a steady and inevitable decline. Buffett was, however, able to harness some of the considerable cash flow of the textile operation (as well as the leveraging possibilities of using the plants as collateral to secure additional capital) in order to begin his legendary string of acquisitions – starting with National Indemnity Company and National Fire & Marine Insurance in 1967… and creating the path that led to acquisitions such as GEICO (Buffett started buying in the late 1970’s… GEICO became a Berkshire subsidiary in 1996).

3) Despite the deterioration within the textile space, Buffett held off closing the final Berkshire textile plants as long as he could. He did this because he recognized the human costs associated with plant closings—job loss and community dysfunction. Because of this awareness on his part, he once indicated that he “would not shut down a business with lower than average profits just to add a small portion to business returns.”

As a consequence, Buffett was able to postpone, but not avoid, the final termination of Berkshire’s involvement in textiles – closing the last mill in 1985.

This proves Buffett’s humanity. Genius or not, not even Buffett can save an industry that becomes structurally unprofitable!

At this point, I imagine some of you from the younger generation are stilling asking yourself: “I can’t believe that Buffett let $0.125 get in the way of his selling all of his stake in a company that (even then) Buffett recognized was facing serious headwinds because it was in a very challenged industry!”

However, consider these salient points:

1) 12.5 cents amounted to a bit more than 1% of the verbal purchase price Stanton had offered!

a. If someone verbally offered you a chance to buy Tesla (TSLA) at $200/share… would you still buy if the offer came in writing at $202/share??

b. That illustrates a parallel circumstance – the price difference is 1% in each case.

2) Imagine an extremely frustrating, annoying person [I used the image of “flint” earlier because I have the feeling that Seabury Stanton had a very “flinty” personality… including being a “skin-flint”!

a. Remember that Seabury’s own brother “sold him out” because Seabury was hard to work with.

b. Anyone who can irritate us that much doesn’t need to work very hard to get under our skin and make us react to things they do in ways which are less likely to be ideal (or even functional) than normal.

c. I am confident that an important element within the Buffett/Stanton dynamic was cross- generational.

i. Buffett was only 34 when he became Berkshire’s biggest shareholder.

ii. Stanton was over twice Buffett’s age (72), and most likely considered Buffett a young whippersnapper who had a lot of gall to just “show up” and start telling him how to run “his” company!

iii. It is easy to imagine that Stanton spoke to Buffett with a condescending tone – which would only serve to irritate Buffett and lead to a mounting sense of mistrust.

3) The following will sound as though I hereby offer a “defense” of Seabury Stanton. However, (trust me) nothing could be further from the truth.[9]

a. For many decades, the smallest increment of price in a stock (which is called a “tick”) was 12.5 cents![10]

b. Presuming he was (as I imagine) a “skinflint”, he might have justified the $11.375/share price specified in his offer letter based on the difference between the normal “bid-ask” prices.

i. However, that totally ignores the reality that this transaction was not executed on an exchange… but was a direct “buyer-seller” transaction.

ii. Stanton thereby either totally ignored the niceties of human psychology[11] or really was an unsavory individual who wanted to get one more “jab” in at Buffett before getting rid of him for good.

iii. Too bad for Stanton that he learned too late that he “crossed” the wrong person!

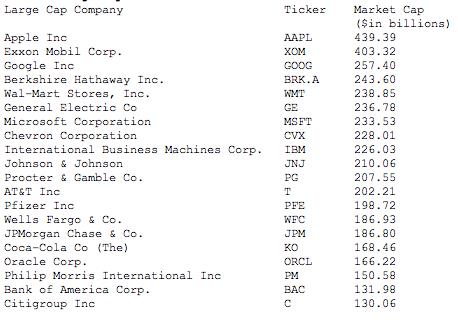

From the perspective of mere mortals like you and me – Buffett’s purchase and total transformation of Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-A, BRK-B) appears to be one of the most outstanding investment narratives of all-time. Currently, BRK-A stands as the S&P 500’s fourth largest company[12], and Warren Buffett has been listed as one of the world’s wealthiest people for as long as I can remember.

However, I don’t need to remind us that we do not “see” with the comprehensive vision of an “Oracle” such as Warren Buffett!

However, I don’t need to remind us that we do not “see” with the comprehensive vision of an “Oracle” such as Warren Buffett!

As Buffett took time in our 21st Century to review the full span of his work, he recognized that he had made some mistakes along the way.

The one I find most interesting is the one Buffett publicly identified in 2010, when he said that refusing to sell his shares to Stanton because of that 12.5 cent discrepancy was the single biggest mistake of his career!

The natural retort to that confession would be: “But Mr. Buffett, everything turned out so magnificently, and Berkshire Hathaway has become a natural and treasured part of our investment fabric! How could that be a mistake?!”

To that, I imagine that Mr. Buffett would offer a kindly smile[13] and then respond: “I have specialized through my career in the optimal use of financial resources. In the short term, my purchases of Berkshire in the early 1960’s were both profitable and helpful in the continuing evolution of my financial skills and the strategies I was developing. However, buying a controlling stake in the company because I was upset with Mr. Stanton was not an optimal use of the financial resources I had available. I should have sold to Stanton and used the cash to invest in other companies or investment vehicles that demonstrated intermediate and long-term growth. As it was, investing in a tired old New England textile manufacturer competing in an industry that was struggling with mounting international competition was not a sound financial decision.”[14]

In his spare hours, Buffett calculated that if he had sold all his Berkshire shares to Stanton and then used that cash horde to start buying insurance companies, his investment dollars would have grown exponentially… rather than (relatively speaking) languishing inside the aging Berkshire infrastructure. Combining the far superior growth prospects of insurance companies with the timeless power of “compounding”, Buffett calculated that his opportunity cost for having spurned Stanton’s offer amounted to approximately $200 billion over 45 years… or about $4.4 billion per year, on average!!

That is a staggering figure! Buffett figures his “mistake” cost more than most company’s annual revenue… and cost that much over the course of 45 years!

All I can say is that I wish I had made a “mistake” that turned out so incredibly well as Buffett’s mistake in buying Berkshire Hathaway!

INVESTOR TAKEAWAY: In my mind, the “takeaways” are very straightforward and include at least the following:

1) There is no “perfect, infallible” investor: if Warren Buffett isn’t “perfect”, then no investor is perfect. And if any investor claims perfection (i.e. makes no mistakes) they are lying and they should not be trusted.

2) It is absolutely essential that we get in touch with our emotions and stay in touch with those emotions. The reason is simple:

a. Investment decisions driven by emotion are almost never the optimal or most profitable decisions.

b. Emotion can blind us from seeing the actual circumstances and full financial dimensions within any given investment option.

c. Emotion can even cloud our evaluation of our investment performance, since human beings are “experts” at rationalizing almost any decision … in order to escape feelings of inadequacy or failure.

d. If we are a trading or investment professional, it may even be advisable to utilize the skills of a counselor or therapist in order to ensure that we are in touch with our emotions and have developed reliable skills to manage those emotions within our investment decisions!

3) The power of “compounding” cannot be overemphasized.

a. It is because Buffett’s “mistake” came at the very beginning of his career that the related opportunity cost is so staggering!

b. If it had come in 1990 or 2000, it would have been (in comparison) a “blip” within his impressive body of work!

[To the left: Early photo of Buffett with his wife]

[To the left: Early photo of Buffett with his wife]

DISCLOSURE: The author has, from time to time, been subject to mistakes himself. Therefore, he empathizes with Buffett. The author has, in the past, owned BRK-B options, but owns none currently. Nothing in this article is intended as a recommendation to buy or sell anything. Always consult with your financial advisor regarding changes in your portfolio – either subtractions or additions.

Submitted by Thomas Petty MBA CFP

[1] Unless one has unlimited resources, every choice must (by necessity) bear the risk of an “opportunity cost” – which Investopedia defines as: The cost of an alternative that must be forgone in order to pursue a certain action. Put another way, the benefits you could have received by taking an alternative action. For example, if I choose to invest $10,000 today in Netflix (NFLX) instead of Amazon (AMZN) and one month from now, NFLX is down 7% while AMZN is up by 7%, my “opportunity cost” is 14% (or $1,400). The term was first used in published work in 1914 by Friedrich von Wiesner (an economist from Austria) in his book: Theorie der gesellschaftlichen Wirtschaft (Theory of the Social Economy).

[2] In the ill-fated year of 1929, no less!

[3] Headquartered in New Bedford, MA.

[4] Some might suggest “from birth”.

[5] Son Jack was company Treasurer, with a presumed “lock” on becoming President upon his father’s (eventual) retirement.

[6] As recorded in a 2008 biography of Buffett entitled The Snowball (by Alice Schroeder).

[7] Otis used to manage the sales operations at Berkshire, but had run-ins with Seabury on a regular basis. The deal between Otis and Buffett was culminated at New Bedford’s finest center for the “elite” – the Wamsutta Club. I imagine that the public nature of the deal rubbed salt in Seabury’s wounds.

[8] Buffett has been handling the annual letter himself ever since then!

[9] After all, A “skinflint” is a “skinflint” is a “skinflint”

[10] The U.S. moved to decimalization (through the Regulation National Market System) in 2001, making $0.01 the official “tick” for all stock priced at over $1.00/share. (Note that “off exchange activity” is not bound by this regulation… so “sub-penny” pricing can occur there (example: “Dark Pools”)).

[11] Namely, that no one takes kindly to the feeling they have been (proverbially) screwed.

[12] Bigger than Walmart (WMT) and only slightly behind Google (GOOG)

[13] As if to say: “Thanks for being kind. But you don’t get my point!”

[14] Not to mention the headwind of falling cotton prices!!

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

Should Dividend Stock Investors Buy Coca-Cola Stock Instead of PepsiCo?

Should Dividend Stock Investors Buy Coca-Cola Stock Instead of PepsiCo?