Historically, stock option premiums generally were quoted in fixed increments of a nickel (0.05) or a dime (0.10), depending on the amount of the premium. But a very successful pilot program led to price premium in pennies instead. And so the days of being “nickeled and dimed” are slowly coming to an end!

The Old Regime

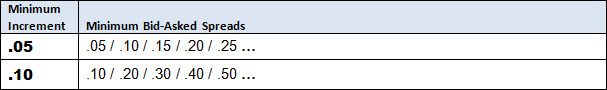

Stock options currently are priced in increments of a nickel ($0.05) for options priced at less than $3.00 and a dime ($0.10) for those priced at $3.00 or more. In fact, if you enter an options order at a price that is not expressed in the proper nickel or dime increment, the order will be rejected.

NOTE: The $3.00 benchmark that divides nickel from dime increments refers to the option’s premium (trading price), NOT it’s strike (exercise price).

Suppose you wanted to buy a call so far out of the money that it has no open interest. The minimum possible quote you could see on that call would be $.05 x $.10, since the premium is less than $3.00 and thus quotation must be made in .05 increments. But—this does NOT mean the bid-asked spread must be .05 or .10! Only the price quotations must be in nickel and dime increments. Since price quotations currently must be in increments of 0.05 or 0.10, the minimum bid-asked spread is one increment, and the spread must be expressed in multiples of that increment. Thus on a $4 premium the minimum spread is 0.10, and the next smallest possible spread is 0.20, then 0.30, and so on. OUCH.

EX: Suppose a call option is quoted 4.10 x 4.50 (bid and asked), a 0.40 spread. A 0.40 spread is huge in this case, almost 10% of the entire premium. You might suppose that dime increments are partly to blame, but such a huge spread really results from lack of liquidity, due to lack of demand. How much difference will penny pricing make in the size of such illiquid spreads? It will be interesting to see, but I doubt we'll see that much difference, because the nickel and dime increments are not, in and of themselves, causing the large spreads on illiquid stock and ETF options. In industry parlance, such illiquid things trade “by appointment only.”

EX: Suppose a call option is quoted 4.10 x 4.50 (bid and asked), a 0.40 spread. A 0.40 spread is huge in this case, almost 10% of the entire premium. You might suppose that dime increments are partly to blame, but such a huge spread really results from lack of liquidity, due to lack of demand. How much difference will penny pricing make in the size of such illiquid spreads? It will be interesting to see, but I doubt we'll see that much difference, because the nickel and dime increments are not, in and of themselves, causing the large spreads on illiquid stock and ETF options. In industry parlance, such illiquid things trade “by appointment only.”

But the really illiquid options are NOT the point. They will always have wide spreads, and it will always suck to trade them. I hope with all my heart that you are not writing calls in such wicked, abandoned options, no matter how fat the premium or net credit on the trade.

The use of large quotation increments results, in my opinion and that of many others, in a less effective and active market for stock options, not to mention picking the pockets of traders and investors. The SEC, which uses the term “penny pricing” for the pilot program, obviously suspected that allowing stock option quotes in penny increments might have the same beneficial effects as it did for stocks.

And indeed, it has.

The Penny Pilot Program

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has long been concerned that the nickel and dime increments lead to larger than necessary bid/asked spreads and result in too-high payments for order flow. Accordingly, the SEC mandated the launch of the Penny Pilot Program, in which options on participating stocks and ETFs (exchange-traded funds, often referred to as “tracking stocks) are quoted in penny (0.01) increments.

NOTE: The SEC in 2001 accomplished a similar sea change in stock price quotations. As you may recall, stocks then were quoted in 1/8th and 1/4 increments. The SEC forced the industry to accept decimalization, meaning quotes in pennies or penny fractions. This change increased liquidity and order flow and has saved investors and traders countless amounts of money. The same problems – high spreads, particularly – infect the options markets.

Elizabeth King, Associate Director of the SEC's Division of Market Regulation, stated in a May 2006 speech that, “Unlike in the stock market, where payment for order flow virtually disappeared following the move to decimal quoting, payment for order flow and internalization practices have become more pervasive in the options markets than they were in 2000. So what does this trend indicate? A firm's receipt of payment for order flow or its decision to route orders to an affiliated dealer does not, by itself, violate best execution obligations. Though, the examinations by Commission staff did reveal that most firms examined have been unwilling to pursue better prices for a meaningful amount of their order flow that may be available in penny auctions offered by several exchanges. A broker cannot ignore price improvement opportunities for its customers because it could impact the payment for order flow or internalization arrangements it has in place.”

That kind of sums it up for me.

The Penny Pilot Program was launched in January 2007 by the options exchanges, on SEC orders. Options on a mere 13 participating stocks and ETFs were quoted in penny (0.01) increments when the option price is less than $3.00 and a nickel ($0.05) instead of a dime for premiums $3.00 or greater, except for the PowerShares QQQ Trust, Series 1 (QQQ), which featured penny increments for all strikes. Why the exception? Incredible liquidity.

Today, about 12 classes—some indices, some equities—are coded as “pennies ALL” and have penny increments for all option strikes. All the other classes in the program are coded as “pennies to 3.00.”

ETFs are exchange-traded funds, which are essentially trusts that issue shares that are very much like equities and trade like stocks. ETF shares track a selected index and nothing else. For example, the QQQ tracks the Nasdaq 100 index.

Got it? Instead of the minimum ticks being .05 for premiums under $3, those in the pilot program have minimum ticks of .01 for under-$3 premiums, so the minimum possible bid-asked spread for them is .01 x .02 instead of the .05 x .10 for those not in the program.

The story gets even better, though! Allow me to quote the SEC’s Elizabeth King again, from way back in 2006:

“Moreover, a limited analysis by the Commission's Office of Economic Analysis indicates that, for the most-actively traded options, the national best bid and offer is at the minimum increment for more than 50% of the trading day [this means the bid-asked spread often was and is as tight as possible, already; at .05 for small premiums and at .10 for premiums over $3.00]. Such statistics suggest that the existing nickel and dime increments are keeping spreads artificially wide. Penny increments could be expected to narrow spreads. And narrower spreads directly benefit customers.”

Explanatory note added by author.

I couldn't have said it better. So if the spreads on options of the most actively-traded stocks were (and are) already as tight as possible for more than half the trading day—then how much better would it be for retail customers (you and me) if that spread were even smaller? So, since the minimum possible bid-asked spread for them is .01 x .02 instead of the .05 x .10 for those not in the program, might not penny pricing lead to tighter spreads?

Just off the top of your head, now, which would you prefer?

The original cohort of 13 issuers now has expanded to about 375 stocks, ETFs and indices as this is written—the classes of securities in the program. The current list of stocks and ETFs included in the Penny Pilot can be downloaded as a spreadsheet from the International Stock Exchange (ISE). You can get the same list of Penny Pilot classes from the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE). The CBOE periodically issues circulars denoting which option classes have been added to or kicked off the pilot program.

In fact, some real oddball things are now in the pilot program. Some of the program classes are equities, some are ETF shares, which are considered equities, and instruments that are included under the rubric of “indices,” such as Bank of America’s (BAC) 3.625% 2016 Senior Notes (BACD).

Who’s in the program? The list is long, but Apple, Google, Coca Cola and similarly liquid issuers, plus of course many ETFs such as the QQQ, SPY, DJX and a handful of indices such as BACD already mentioned and others such as the CBOE Mini-MNX Index (MNX, or “minx”).

The pilot program lists are worth checking out. Certainly, I’m not saying that everything on there is good for call or spread writing. But they are the most liquid population of options available.

But just as certainly, my preference is to write options on stocks and ETFs that are in the pilot program, since pricing, fills and spreads are better. In fact, I don’t do much trading at all in options outside the program. Why would I? Options with penny pricing have vastly more liquidity, fairer prices due to real market demand and traders experience less slippage (price degradation in the process of getting filled)–among many other advantages.

The Penny Pilot Program has been a solid success, in my book and in the views of virtually all commentators—and I say “virtually” only because there just might be one that still opposes penny pricing. The program’s consistent expansion is clear evidence of its utility. If you’re wondering why it’s still a pilot program after seven years, so am I.

But let’s be clear: no rule or program can create demand and thus liquidity; and options nobody wants will still have poor liquidity, big bid-asked spreads and all the other things attending low demand.

So, How’s It Working?

As with any new thing, the Penny Pilot Program had its supporters and detractors when it launched. The naysayers (ex: the Options Committee of the Securities Industry Association) contended that penny pricing would disadvantage us retail investors in comparison to institutions and professional traders—and that penny increments will hurt liquidity and result in poorer execution of option trades. Well, har.

It must be remembered that the brokerage industry also predicted that decimalization would bring about the death of the American stock market, when in fact decimalization was a huge winner for traders and investors, especially us retail players. The only losers in decimalization were the market makers that no longer had a fat profit automatically built into every trade.

Proponents like myself believe that penny pricing has resulted in more competitive pricing, reduced payment for order flow, reduced costs and tightened spreads, pretty much the same way decimalization did for stocks. Despite the dire predictions of the brokerage industry, the sky (once again) has not fallen and the market makers haven’t all left the options business in disgust. In fact, they’re making a ton of money, because these SEC-mandated quotation rules are a meaningful cause of the explosion in options trading.

To illustrate my concerns about the current nickel and dime quotation increments, let's take a look at some simple, everyday examples. Our first example underlines the point that daytrading in particular and the surge in retail investing in general never could have arisen without decimalization of the stock markets.

Example: Suppose back in the 1990s before decimalization a retail trader had bought stock at 20-3/8, then decided seconds later the trade was a mistake and immediately sold the shares, without there being any change in the stock's price quotations in the meantime. The trader would have gotten only 20-1/4, because when stocks were quoted in 1/8th increments, 1/8th was the minimum possible spread between the bid and asked prices.

Why, that eighth doesn’t sound like all that much, right? The brokerage industry relied upon retail investors not getting it—traders always knew. But that eighth is 0.125, which is like a $12.50 tax on every round lot. No wonder the industry opposed decimalization.

THAT is the effect that fixed increments have. They create artificial spreads, which benefit the market makers, never you and me. It is tougher to make money when the market is taking that kind of spread out of your hide.

Now think about the relative proportions of these increments to the price of the stock or option: a 0.10 quotation increment is far greater in proportion to a $5 option premium than the old 1/8th (0.125) increment was to a $20 stock, for example. If a 1/8th increment is abusive or at least inefficient on a $15 stock, what should we consider a 0.10 increment on a $3.25 option premium?

A better—or I suppose worse—example yet: how about a 0.05 increment on a $0.30 premium? That is the increment for premiums under $3.00 on option classes NOT in the pilot program. In that example the 0.05 increment, and thus the absolute minimum spread, is fully 1/6th the entire premium. Isn't that just faintly outrageous? Wouldn't a one- or two-cent spread be far more advantageous to the trader? Duh.

OK, point made. Tighter option spreads due to penny pricing have meant that the quotes are fairer and the spread much smaller to begin with. Options trading activity has only continued to grow.

Thoughts on Shaving Pennies

If you write covered calls or trade options on any option classes in the Penny Pilot program, the penny increments allow you to place a tighter order where the premium is less than $3.00. When a covered call or spread writer enters a net debit order on trade entry (meaning that the limit price entered is the debit after netting the call premium against the stock price, or the stock option prices are netted), there already is some price flexibility.

EX: If the stock is $20 and I want to write the 20 Call bid at $1.00, I can enter the order as a net debit limit with reasonable assurance of a quick fill if the limit entered is $19.00 – that, after all, is the market in this example.

I might, however, enter the order as $18.95, or $18.97, say, in an attempt to pick up a few extra pennies, since the smaller the debit – the less I pay – the better the return I stand to make.

I leave it to the broker to get the order filled, shaving the pennies on either leg of the trade, or both—I don't care where. Keep in mind that the stock order in a covered call is going to a stock exchange or market maker in the stock, while the option order goes to an options exchange or market maker. It's not as if the same market maker or specialist is handling both the stock and option order, thus there is no one entity that can “net” out the two legs of a covered call trade.

This applies with equal force to other option trades, of course. I’ve got an idea: let’s go to penny pricing for all premiums on pilot program stocks and indices options, instead of just a few.

To learn more about how to generate income consistently, click here.

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

Airbnb Is Down 25% From Its 52-Week High. Is It a Bargain or a Trap?

Airbnb Is Down 25% From Its 52-Week High. Is It a Bargain or a Trap?