In Part I of our extended look at the current investment world of China, we took great pains to offer a balanced view of the strengths and weaknesses of China, its economy, and its markets. There is absolutely no doubt that, as the world’s second biggest economy and its largest populace[1], China gets more than its share of news stories, as well as an enormous number of references within stories about other economies, nations, and regions.[2]

Over the years, Chinese leaders have recognized (to one degree or another) the need to “reform” the Chinese economy and empower it with a greater degree of the “freedoms” that drive Western capitalist economies. In the past decade, various reforms have been announced and worked into the system – a stupendous improvement over the infamous (and perpetually failed) “Five Year Plans” that defined the Chinese economy in the days of Chairman Mao.[3] However, every Chinese political leadership group (cadre) has placed a high degree of importance upon being “in control”, resulting in a delicate “balancing act” between economic freedom (on the one hand) and political control from Beijing on the other hand. Needless to say, that balancing act has experienced numerous “bumps” along the way – some bigger and more notable than others![4]

One year ago (in November 2012), the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (中國共產黨第十八次全國代表大會) in Beijing resulted in a major political transition.[5] Due to the combined impact of age limits and term limits, seven of the existing nine members of the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) retired from office! Add to that mega-shift within leadership a key reform in the total prescribed number of PSC members (reduced from nine members to just seven) – and you have about as wholesale a shift in political leadership as a major world nation is likely to willingly experience.

One year ago (in November 2012), the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (中國共產黨第十八次全國代表大會) in Beijing resulted in a major political transition.[5] Due to the combined impact of age limits and term limits, seven of the existing nine members of the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) retired from office! Add to that mega-shift within leadership a key reform in the total prescribed number of PSC members (reduced from nine members to just seven) – and you have about as wholesale a shift in political leadership as a major world nation is likely to willingly experience.

The most powerful political leader in China is the one who holds the position of General Secretary of the Central Committee (of the Communist Party). For the five years ended last November, Hu Jintao was General Secretary. However, during the past year (and for four additional years), Xi Jinping has served as the General Secretary and continues to establish his hold on power (see his image to the left).

The most powerful political leader in China is the one who holds the position of General Secretary of the Central Committee (of the Communist Party). For the five years ended last November, Hu Jintao was General Secretary. However, during the past year (and for four additional years), Xi Jinping has served as the General Secretary and continues to establish his hold on power (see his image to the left).

This month, following a major Chinese leadership meeting in Beijing, the government announced a new set of economic and investment reforms in its usual fashion – through the release by Xinhua[6] of a lengthy document that outlines the details. It is not typical for China politicians to exceed expectations – at least on the positive side; however, by most accounts that I have read, these newest reforms are more promising than expected!

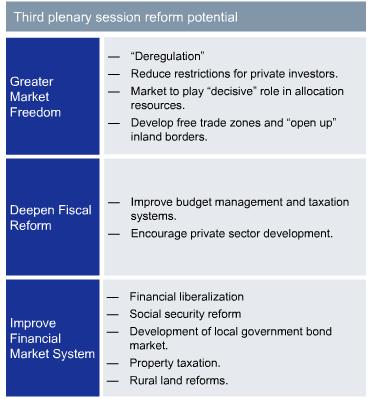

For those whose patience runs thin quite quickly, here is the “Reader’s Digested Condensed” version of the latest reforms:

MARKET REFORM:

MARKET REFORM:

Many experts were pleasantly surprised by the inclusion of “pricing reform” – code for the removal of a very extensive range of existing price controls that the government has managed in years past. As we know in the West, letting “price” seek its own market-determined level maximizes (in the big picture) the optimum allocation of resources.

Similarly, accelerating yuan convertibility and interest rate reform (treasury yield curves) should enhance efficiency and China’s economic interaction with global partners.

In addition, an increase in trade free zones should enhance economic activity.

FISCAL REFORM:

Holding local and regional governments accountable for efficient budgeting and tax management could significantly improve the economic ecology within China – utilizing fewer resources on government and more resources generating economic productivity.

Expecting and fostering an increased level of private sector development should similarly result in more efficiency and productivity.

The new reforms explicitly incorporate measures to transfer more resources and control from “state-related” entities to private enterprises. This includes permitting non-state involvement in government projects and the proactive fostering of the trend toward a “mixed ownership economy”!

Hopefully, this will result in a steady diminishment in the number and reach of SOEs (“State Owned Enterprises”). Significantly, these reforms announce an increase in the share of SOE profits that become used for public finances (such as social security) – from the present 15% to a new level of 30%!

FINANCIAL REFORM:

Legislation is promised for a property tax, as well as other related reforms that could level out some of the “bubbling” that we referred to in Part I with regard to excessive property development and housing construction. It is expected that tying a property tax to ownership of a home will have the impact of decreasing the appeal of the speculative buying of homes in China.[7] This should also increase the economic appeal (on a relative basis) of allocating capital to non-real estate assets (thereby “leveling the playing field” among investable assets!).

Another major development is the empowering of local governments to issue bonds (as well as expand other financing channels) for public works and construction projects.

POPULATION REFORM:

The popular press has made far too much of the continuing reforms announced with regard to the “one-child policy”. It is true that a “one-child policy” is much more easily understood[8] than the many more significant, but more complex, finance and economic reform. However, the population reform announced in this reform package (loosening the one-child limit) only applies to certain couples.[9]

More significant than “one-child” reform is the acceleration within Hukou enforcement[10]. This will enable an increased flow of individuals and families from rural China into urban China – including some of those “ghost cities” we highlighted in Part I.

POLITICAL AND LEGAL REFORM:

If the reforms described below actually take hold and thrive, they might conceivably become (over the long term) two of the most powerful of these newest reforms:

1) Reduce the power of local governments over the court system and move toward an independent and fair judiciary system.

2) The strengthening and enforcement of prohibitions against corruption in government (and presumably (one could hope) within corporations as well).

So, these are the highlights from the 20,000-word government press release on “Reform”! It will be fascinating to watch Beijing government over the next 12-24 months … discerning during that time the degree to which Xi Jinping and his political cadre allow market and economic forces to play themselves out without interference!

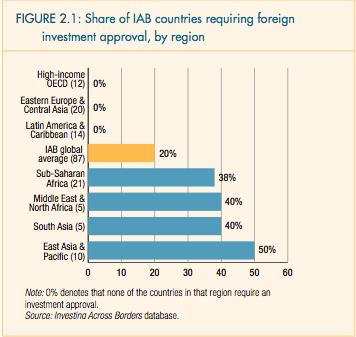

As we wrote in Part I, governmental restrictions on foreign ownership in China have been very limiting (if not stifling). Just to be fair, China is not alone in enforcing this type of policy. Below is a chart[11] that displays the extent to which different world regions restrict “Foreign Direct Investment” (FDI). The benchmark is the world average, represented by the orange line (20%). Note that South Asia [12]is tied with the Middle East and North Africa at 40% (twice the global average). Which region do you suspect has the most restrictive regulations on FDI??

BINGO! – the region that includes China (East Asia & Pacific), has a restriction level of 50% (two and one half times the global average).

BINGO! – the region that includes China (East Asia & Pacific), has a restriction level of 50% (two and one half times the global average).

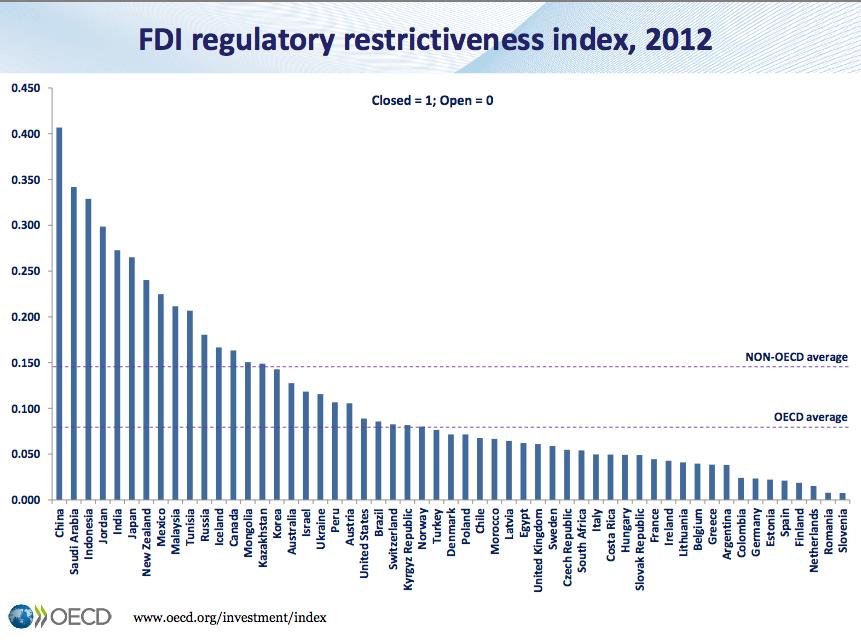

That chart is certainly telling. However, there is a chart that is even more revealing … a chart that is found within the website of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD):

The key takeaways from this chart include the following:

1) China is practically “off the charts” (relative to all the other countries), very securely sitting at the top on the “restrictive foreign investment policy” metric!

2) Non-OECD countries are (on average) less than half as restrictive as China (that is remarkable!).

3) OECD countries (on average) are less than one-quarter as restrictive as China.

I think this data gives you a solid perspective on the extent to which China has restricted foreign investment. At the equity market level, that restriction has impacted the Shanghai Stock Market Exchange ever since it was founded, but it has not limited the Hong Kong Stock Market.[13]

However, this inequitable regulation of the Chinese markets has now become significantly loosened!

“But wait,” you say. “I own an ETF of Chinese equities. There aren’t any restrictions! What on earth are you talking about?”

At the risk of disillusioning anyone who has been depending for years upon the transparency and integrity of Wall Street and investment firms, the fact is that prior to November of 2013, anyone owning such funds has actually held some combination of shares from the Hong Kong Exchange (the world’s sixth biggest), the tiny Taiwan Exchange (just one quarter of the trading volume of Shanghai), or some form of equity derivatives! Foreigners have not been permitted to directly invest in the so-called “A Shares” of the big Chinese corporations that trade only through the Shanghai Exchange!

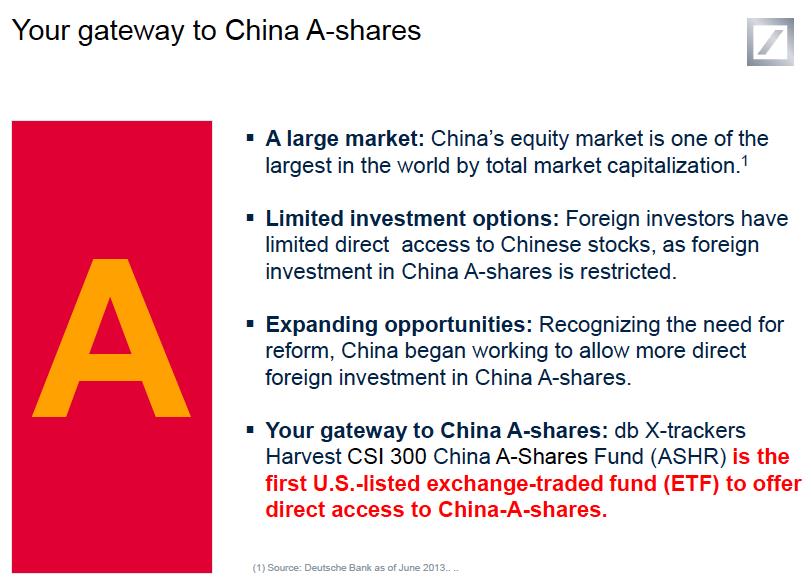

As of this November, that has changed! U.S. investors can now invest directly in Chinese A-Shares through a totally new ETF – the db X-trackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares Fund (ASHR).[14] Indicative of the slow evolution toward economic openness and freedom in China is the fact that Deutsche Bank had to partner with a Chinese-controlled asset manager in order to receive permission to create this ETF. As it happens, that requirement may prove to be beneficial to ASHR, since its internal (ie. Chinese-owned) partner is Harvest Global Investments Limited – a wholly owned subsidiary of Harvest Fund Management.[15] As we learned in Part I, the heritage, culture, customs, and mores of China are mysterious enough to Westerners that having an active partner who can offer “insider” insights and guidance should prove accretive to fund performance and investor confidence!

As of this November, that has changed! U.S. investors can now invest directly in Chinese A-Shares through a totally new ETF – the db X-trackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares Fund (ASHR).[14] Indicative of the slow evolution toward economic openness and freedom in China is the fact that Deutsche Bank had to partner with a Chinese-controlled asset manager in order to receive permission to create this ETF. As it happens, that requirement may prove to be beneficial to ASHR, since its internal (ie. Chinese-owned) partner is Harvest Global Investments Limited – a wholly owned subsidiary of Harvest Fund Management.[15] As we learned in Part I, the heritage, culture, customs, and mores of China are mysterious enough to Westerners that having an active partner who can offer “insider” insights and guidance should prove accretive to fund performance and investor confidence!

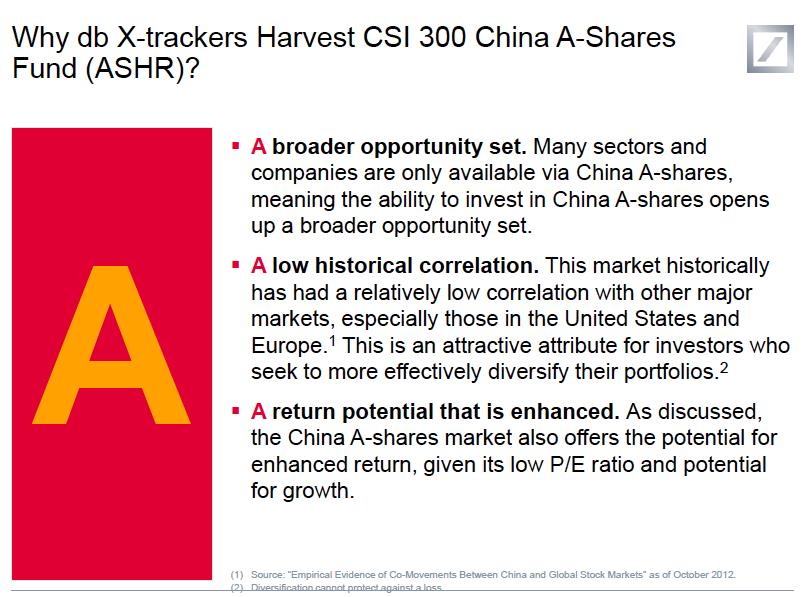

From the ASHR website, here are some of the rationales (investment themes) offered by the marketing department at Deutsche Bank for investors to consider as they perform due diligence on ASHR:

A price chart from YahooFinance.com contrasting ASHR (in blue) with the S&P 500 Index from the first day of trading in ASHR reveals two things:

1) the degree of positive reaction by the market to the news regarding Chinese economic reforms (ASHR up a very quick 8%); and

2) ASHR’s potential to “move” relative to the S&P 500 (more than tripling the S&P’s none-to-shabby 1.5% return in less than one month).

To wrap up our look at ASHR, let’s review some of the metrics touted by Deutsche Bank as part of a bullish case for investors to consider vis-à-vis an investment in China A-Shares.

To wrap up our look at ASHR, let’s review some of the metrics touted by Deutsche Bank as part of a bullish case for investors to consider vis-à-vis an investment in China A-Shares.

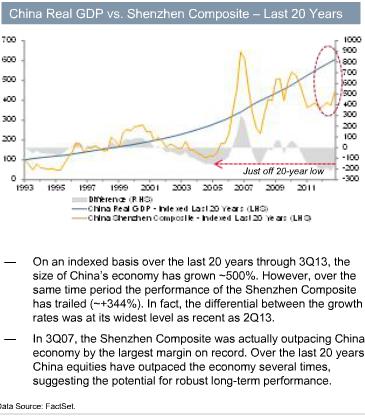

Here is a retrospective look at the economic growth of China (Real GDP) compared with the price performance of Chinese equities.[16] The premise of this chart is that equities (the yellow line) are currently significantly undervalued vis-à-vis economic growth (the grey/blue line) … and the broken red oval at the right of the chart highlights the differential.[17]

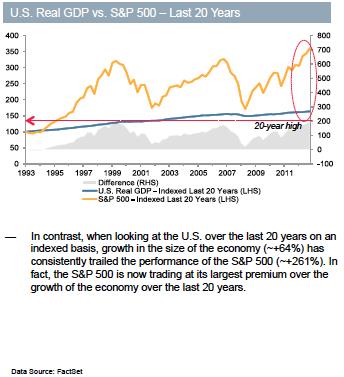

In order to provide you with a telling point of reference, below is a parallel graph that contrasts U.S. stock performance with the trend in Real U.S. GDP over the past 20 years:

The red oval on the U.S. chart highlights a huge differential between stock price appreciation and economic growth… with stocks having soared that much above the economic trend line.

Obviously, Deutsche Bank is suggesting to us that China equities offer a compelling “value” when compared with U.S. stocks. I would not necessarily dispute that. However, I would most definitely point out that the most obvious market force illustrated by this chart is the nearly untold power of Ben Bernanke and the U.S. Federal Reserve to actually drive U.S. stock prices upward!

Obviously, Deutsche Bank is suggesting to us that China equities offer a compelling “value” when compared with U.S. stocks. I would not necessarily dispute that. However, I would most definitely point out that the most obvious market force illustrated by this chart is the nearly untold power of Ben Bernanke and the U.S. Federal Reserve to actually drive U.S. stock prices upward!

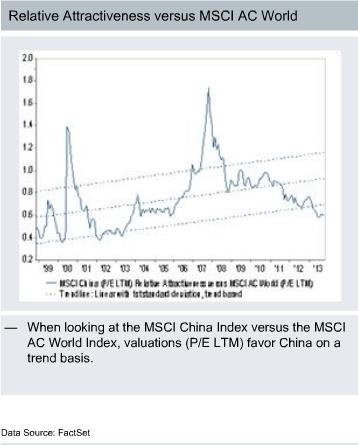

This chart graphs (on one line) the MSCI China Index relative to the MSCI AC World Index over the past 14 years. As you can see, the graph currently demonstrates that China is undervalued when compared with the much broader World Index!

This chart graphs (on one line) the MSCI China Index relative to the MSCI AC World Index over the past 14 years. As you can see, the graph currently demonstrates that China is undervalued when compared with the much broader World Index!

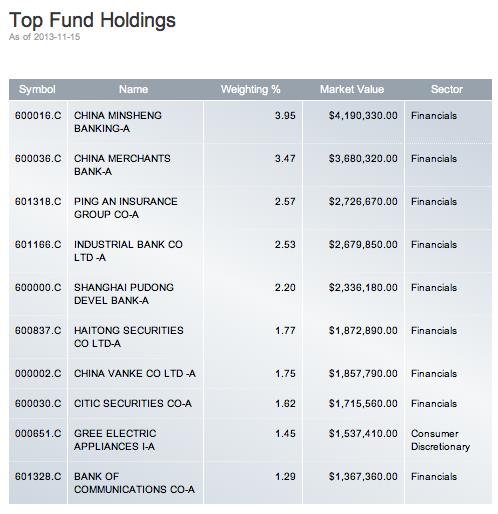

ASHR offers a list of its ten largest positions on its website (see below). Note that none of these companies are the ones we hear about most frequently on CNBC. I do not intend this observation to be, in any way, a criticism of the ASHR ETF! Instead, I just want to point out that the “real” Chinese equity market is significantly different than the impression created in our minds by the U.S. financial press, which consistently dwells upon stocks like Baidu (BIDU), Sina (SINA), Youku.com (YOKU), Yingli Green Energy (YGE), Renren (RENN), Qihoo 360 Technology (QIHU), New Oriental Education & Tech (EDU), China Mobile (CHL), NetEase (NTES), Focus Media (FMCN), CTrip.com Int’l (CTRP), China National Offshore Oil (CNOOC), etc.

As you might guess, most of the ten securities above are among the largest companies (by market cap) in China. As we’ve said, Beijing restrictions have previously made these stocks off-limits to Westerners, so ASHR is our “first crack” at buying into the “real” China.

I only have one more slide from the ASHR site, summarizing a few of the points that I have already outlined for you above (the slide is self-explanatory):

INVESTOR TAKEAWAY:

Let me emphasize that, contrary to appearances, I have not become a shill for Deutsche Bank, Harvest Fund Management, ASHR, or even Xi Jinping. This two-part series was prompted solely and totally because of the loosening of Chinese financial controls and the broadening of foreign investment in Chinese markets.

If the U.S. vice president thinks that ObamaCare was a big deal[18], then let me offer this thought. As we consider the long sweep of Chinese history (referred to in Part I) and the 63-year long history of tight control by the strong political cadre in Beijing, this latest set of reforms and the opening up of the Shanghai Stock Market Exchange to broader Western investment is similarly just as big a deal![19]

As I wrote earlier, the next two to three years should provide much “grist” for the mill of researchers at think tanks, academics and post graduate students in universities, and the more astute and articulate of the commentators in the financial press. We will soon be reading fascinating reports on how these reforms have impacted stocks, bonds, economic growth, and the quality of life in China. We can also count upon many upcoming analyses regarding how the government handles the consequences of these reforms as they unfold.

Let me alert you in advance that we must be prepared for many of these stories, study summaries, and analyses to conflict with one another. We should also steel ourselves for the certainty that much of what we’ll read (or hear) in the “popular” Western press in the months ahead will be no less “off target” than the material we’ve been reading there for decades. Therefore, I urge you to be very discerning with regard to which journalists, analysts, publications, and authors you decide to rely upon for your understanding of contemporary China!

Finally, if you invest in ASHR at all, I suggest you choose to invest only money that you can afford to lose. This is not to suggest that ASHR contains particularly risky securities, but only to serve as a reminder that ASHR has a record that stretches back only one month! I consider it a personal “rule” not to invest in any fund or ETF until it has established a “record” of at least 6-12 months. It is a corollary to my rule to avoid buying a software upgrade until enough time has passed for the inevitable “bugs” to (for the most part) be discovered and resolved. Just call this rule a part of “Risk Management”.

DISCLOSURE: The author’s portfolio still bears enough “scars” from past trading in Chinese equities/funds to remind him of the caution that is always wise when investing in China. He currently does not hold any large positions in any Chinese equities. However (as you’ve guessed from the above) he finds these new reforms fascinating and will be watching ASHR with great interest in the months ahead!

Nothing in this article is intended as a recommendation to buy or sell anything. Always consult with your financial advisor regarding changes in your portfolio – either subtractions or additions.

Submitted by Thomas Petty MBA CFP

[1] Therefore, the world’s potentially largest and most profitable consumer base!

[2] Within such stories, China is often (rightly or wrongly) blamed for lower production, export, or profit metrics because China has not been growing at quite the rate that it did two or three years ago.

[3] As I grew up during the 1950’s and 60’s.

[4] For example, we referred to Google (GOOG) in Part I, which refused to bow to government pressure to help it suppress free expression on the Internet in China. That resulted in GOOG leaving China (I describe it as “kicked out”), a development that continues to have repercussions today… one being that the new Motorola phone can’t be sold in China because Motorola is owned by GOOG.

[5] The photo from the 18th National Congress comes from Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/18th_National_Congress_of_the_Communist_Party_of_China) as does the photo of Xi Jinping.

[6] The official Chinese state news agency.

[7] This is a complicated issue, but one economic dynamic in China that has been in play for years now has been investing one’s cash into homes (for some folks, it serves as their preferred method “to save”). That, combined with a relatively high savings rate in China, has put upward pressure on housing prices.

[8] By the average reader…

[9] Namely, couples in which one of the parents was an only child may give birth to two children!

[10] Every person and family in China (for many centuries) has been “registered” to live in a certain area/region/town of China. They were not permitted to move elsewhere without permission. This Hukou policy was a central lever used by Beijing for the past 40-50 years to control the pace of urbanization and to ensure that enough citizen remained farmers to ensure food sustainability.

[11] Source of this chart is “Investing Across Borders” (IAB).

[12] For example, Vietnam (one of the best performing emerging market equity markets this year) limits aggregate foreign ownership of any company to no more than 40%!

[13] Reflecting on the history of Hong Kong as a British colony provides us a simple explanation. The Hong Kong Market was such a strong, striving economic force at the time of the transfer to China that even the overly controlling leaders in Beijing recognized the folly in clamping down on the exchange!

[14] The “db” indicates that the ETF belongs to the Deutsche Bank family of ETFs. The inception date of this ETF is 11/06/13. In these initial days, it has managed at least $107 million. The annual management fee is 0.80% (not atypical for similar foreign funds) and the total expense ratio is 1.08%.

[15] China’s second largest asset manager by asset size! More specifically, Harvest has managed various China A-Shares passive strategies for eight years … including 11 mutual funds and seven ETFs that managed over $10 billion at June 30th of this year.

[16] The equity performance data used in this chart comes from the very small Shenzhen Exchange.

[17] Source of the data used is “FactSet”.

[18] You all remember, I’m sure, the very colorful adjective he added to emphasize just how big a deal it was!

[19] My editor may go a bit nuts about this comment, but I find it ironic (and more than a bit appalling) that as the Chinese government loosens its grip on the independence of its people and markets, the U.S. (by all appearances) is doing precisely the opposite!

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

Saving for Retirement? Here's the Number You Should Be Aiming for, and How to Get Your Portfolio There.

Saving for Retirement? Here's the Number You Should Be Aiming for, and How to Get Your Portfolio There.