We each know what its like to have a terrible day or week in the market – hand wringing, thoughts of “if only this or if only that…” or thinking “How could I be so stupid?”[1]

But I want to make you feel better about yourself and your trading! As we know, one of the best ways to do that is through the “compare and contrast” methodology.

In that spirit, let me offer this thought: “If you felt as though the market ‘beat you up’ in mid-October (the SPY low was on October 16th) – take heart! At least your stock didn’t lose you almost $910 million in one day… and $2.5 billion between its April 14th YTD high and the closing price on October 24th!!!

So see how much better a trader you are than the person who lost all that money?

I can tell by the look on your face that you realize there must be an essential fallacy in the illustration I chose in my attempt to lift your spirits!! In fact, you are correct!! The investor who incurred that incredibly huge unrealized loss bears as much resemblance to you or me as whale bears to a tadpole.

However, I used this story as a way to draw your attention to several essential truths about trading and investments:

1) No one can predict with certainty what will come in the market looking forward! There is no one with “20/20 Market Vision”!

2) Consequently, we must always be well-diversified and invest within the bounds of our personal risk tolerance.

3) There will always be differences of opinion regarding what constitutes “solid value”, or even which stocks should be considered true “Blue Chip” stocks![2]

4) The ultimate goal of a company should be to utilize its financial resources in those projects, businesses, and/or investments most likely to earn “excess profits”[3]. And, of course, those choices should be made in ways that are sustainable. [You’ll soon see why I emphasize that point.]

By now the most astute among our readers have likely deduced that the “investor” in our beginning illustration is none other than Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. (BRK.B) and the stock holding through which he has incurred those mammoth unrealized losses is IBM (IBM). In fact, Buffett owns over 70,174 shares of IBM – accounting for just over 7% of all outstanding IBM shares.

Interestingly, Buffett has long held a deep aversion to investments in “technology” but laid that aversion aside in 2011, when he started accumulating his current stake in IBM. At the time, he expressed his confidence in the value inherent in the company’s famous brand, and he extolled the “stickiness” of their customers. Unfortunately for Buffett and his fellow IBM stakeholders, by the 2nd Q of 2012, IBM reported a Year Over Year (YOY) reduction in its revenues… and that trend has continued, unabated … ever since.

This year’s 3rd Q report was released on October 20th, and shareholders now wish that a decrease in revenue for the 10th straight quarter had been the only bad news in that report. Unfortunately, the report

1) Diluted (GAAP) Earnings Per Share (EPS) were down by 8%;

2) Revenues were down by 4% (to $22.4 billion)

3) Total Operating Expenses were up by 2% YOY (adjusted for acquisitions and currency fluctuations, “base expenses” were flat.[4]

4) When I first heard this news, I nearly swerved off Interstate 40. IBM announced that it had paid GlobalFoundries $1.5 billion to take its semiconductor foundry in Fishkill, NY off its hands! My first take was that I misheard the story or the reporter accidentally said “paid” instead of “received”. After all, a July story on the New York-based TimesUnion.com website had reported a projected sale price as high as $2 billion coming to IBM. Soon enough I discovered that IBM management recognized it would continue to need the chips produced there, but didn’t have the luxury of absorbing the annual losses coming from that part of the IBM operation. Evidently, that was a big “Catch 22” like issue for IBM. The transaction prompted a $4.7 billion charge off.

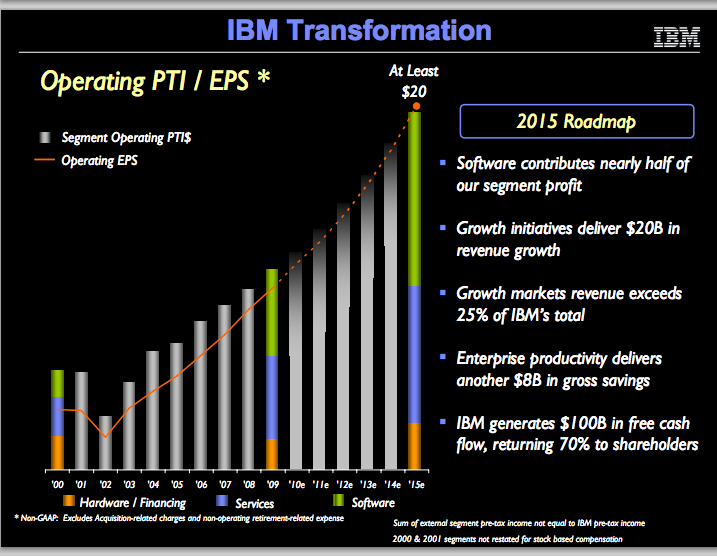

This is the cover of the splashy report from then CEO Sam Palmisano in 2010... "promising $20/share by 2015.

5) This quarterly report witnessed an extremely awkward moment when the current CEO Virginia Rometty admitted that management was not going to be able to deliver on former CEO Sam Palmisano’s “pledge” in 2010 that IBM’s earnings would grow to $20/share by 2015. That pledge had been rolled out in 2010 with great fanfare… including lots of impressive looking corporate charts projecting this action and that action… all of which would almost inexorably lead to that $20/share figure. The presentation had been titled: “Roadmap 2015”. This past week a large employee group released a public statement describing it as “Roadkill 2015”… enumerating ways in which the plan hurt the long-term health of IBM.[5]

6) With such gruesome numbers, Rometty was forced to admit that there was “a falloff in September of customer buying behavior.” An objective observer might have surmised that ten straight quarters of shrinking revenue might have been rooted in some such “falloff”. So much for customer “stickiness”.

Here is a detail page from that 2010 "Roadmap 2015". Mr. Palmisano could be the "poster child" for the dangers of "forward-looking" numbers and promises to shareholders. However, current CEO Rometty will be remembered as the one who had to admit the "promise" couldn't be kept.

That isn’t all the bad news from that report… but surely enough to convince you tat Excedrin sales must have ballooned in and around Armonk, N.Y. (IBM headquarters) both before and after the report.

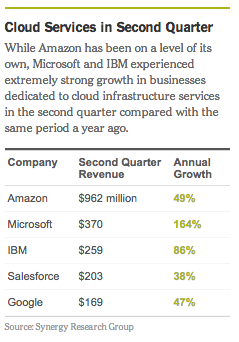

And lest you think I am incapable of finding any silver lining – the metrics on IBM’s “Cloud” business segment were stellar. The prior quarter saw revenue increase over 80%, and this quarter they increase over 50%. That is (needless to say) promising.

In 2013, IBM paid $2 billion for SoftLayer, a leading Cloud vendor. Since then, through that channel, IBM has been offering Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), Platform-as-a-Service, Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), and Process-as-a-Service. Combined with IBM’s own Cloud capabilities, that purchase has catapulted IBM from the “back of the pack” in the space to one of the top handful of Cloud players… as these “Gartner Magic Quadrant” slides show – contrasting 2013 with 2014. [The key to the graph is knowing that the “leaders are those in, or closest to, the top right quadrant.]

The acquisition of SoftLayer propelled IBM upward and to the right by 2014's ranking. IBM can now compete with AMZN and MSFT in the Cloud.

There are two major caveats I need to inject at this point about the Cloud.

1) First of all, as the data below indicate (offering 2Q 2014 Cloud Revenue from major providers), we have to keep the Cloud revenue in perspective relative to the rest of IBM.

Let’s do a “paper napkin” calculation for IBM:

a) 3rd Q Cloud Revenue grew by 50%

b) That number must be around $390 million.

c) Total 3rd Q Revenue: $22.4 billion

d) Cloud Revenue is therefore about 1.7% of total Revenue.

2) Neither the vendors nor the board in charge of GAAP Standards have come to a commonly accepted methodology of accurately and transparently accounting for “the Cloud”.

In fact, the SEC initiated a probe of IBM’s accounting within its Cloud operations, to determine if the company violated any regulations or standards. This past June, IBM was cleared of wrong doing – but the probe is suggestive of how “murky” accounting standards are (currently) vis-à-vis the Cloud. Therefore, there is no dependability comparability among the major vendors… and various analysts and accounting specialists use different sets of assumptions when creating Cloud financial metrics.

That being said, this exciting growth within the IBM Cloud operations is a source of hope for the future. However, when more folks work for IBM than live in Raleigh, NC, Omaha, NE, Miami, FL, or Oakland, CA… it will take an awful lot of “Cloud” revenue and earnings to “turn the ship” around.

In researching this article, I scoured a lot of resources, with views offered from a wide spectrum of writers – several optimistic, some neutral, and a couple of them not happy at all with IBM. I decided that I wanted to attempt a “middle way” analysis. However, in order to measure anything, we know that we need an objective standard by which to measure. What should that “objective standard” be?

Let’s turn to past IBM Annual Reports to see if they offer a clue. Watch this progression of references with regard to “market value”

1994 Report Market value is “our key report card”

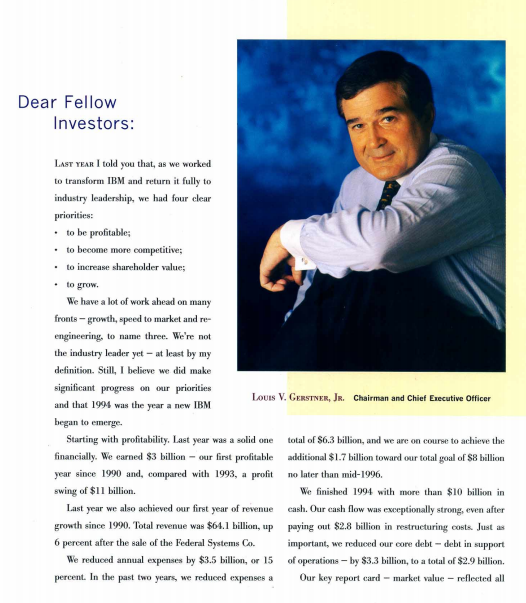

Featuring then CEO, Louis Gerstner, this is the page from the 1994 Annual Report in which Gerstner establishes "Market Value" as the key "Report Card" for IBM. See bottom right.

1995 Report “One of the best indicators of our progress.”

1996 Report “Our ultimate report card.”

1998 Report “Probably the most important measure of progress to investors.”

1999 Report “Probably the most important measure of progress to investors.”

Very interesting, correct?!

However, by 2002, the then new CEO, Sam Palmisano, wrote: “It [market value] held up better than those of all our principal competitors.” Then in 2003, Palmisano reiterated the import of market value and promised to tie that to the granting of executive stock options. Market value has not been mentioned as any benchmark since 2003. Let’s explore why.

Before I share the following graphs, I want to add the important caveat that every presentation of data can reflect a bias. That is not meant to convey any pejorative judgment upon these graphs… it is merely reminding us of an elemental human truth. I owe a great debt to Peter E. Greulich for his time consuming work in researching and creating these data rich graphs. The graphs first appeared in past articles by him published on the SeekingAlpha.com website.

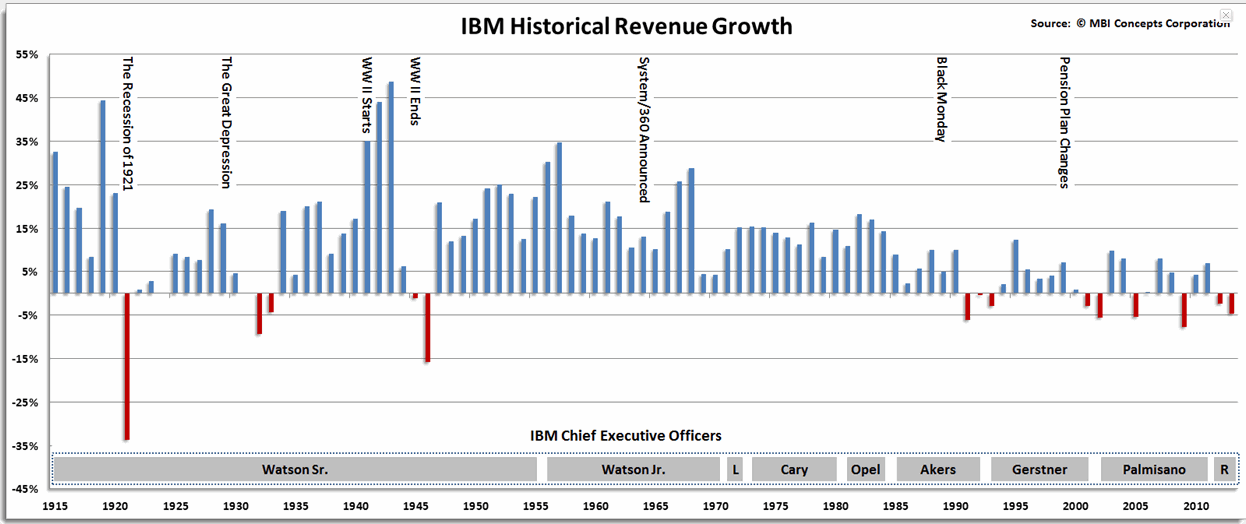

First, IBM’s time as “grower of revenues” is long past. That is a function of its size:

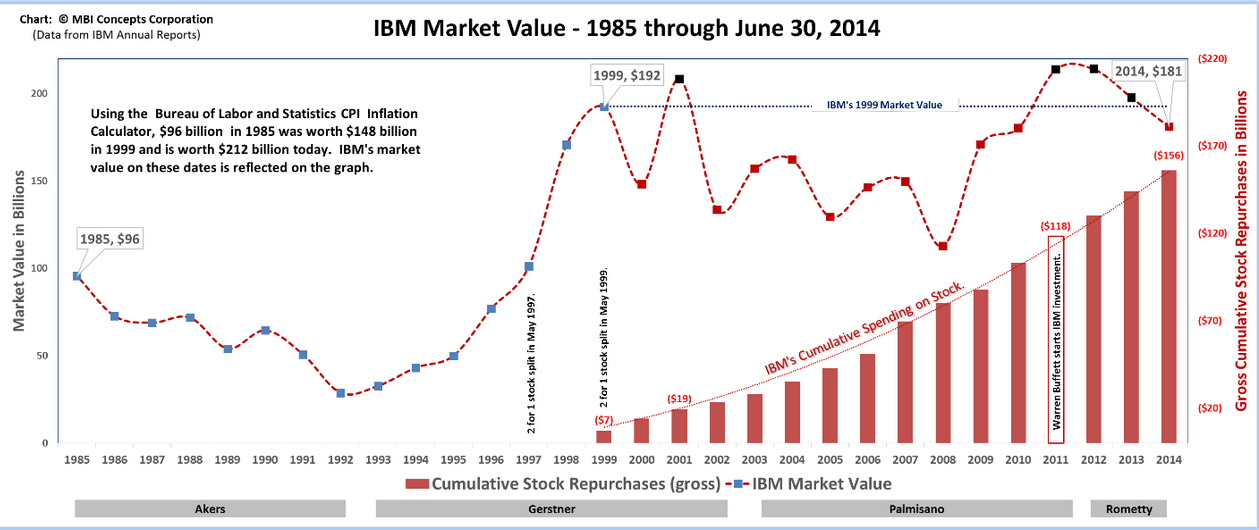

Second, we are all conversant with how popular “returning value to shareholders” has become – most commonly through share buybacks and/or dividend increases. IBM has been a proponent of each. Here is a seemingly complex graph that paints a fascinating picture of multiple variables all at once:

1) The dotted line is represents IBM’s market value each year from 1985 ($96 billion) through the present.

a) As a standard of measure, Greulich calculated what the market value would be in 1999 and 2014 if it kept pace with the Bureau of Labor Standards (BLS) CPI metric.

b) For now, assume the “adjusted figure” as a way to benchmark a minimum growth level in market value through the years.

i) In other words, the “return” to investors would be the annual dividend, while the company’s market value would keep pace with inflation.

c) For 1999, that “inflation matching” market value would have been $192 billion;

d) If IBM market value had kept pace with inflation, today’s value would be $212 billion.

i) Alas, the actual value is $181 billion… even less than the inflation matching number calculated for 1999, much less the number for 2014!

2) Now take a look at the solid red bars starting in 1999 and continuing into today!

a) Those bars represent the level of “Share Buyback” expenses during those years… on an accumulated basis.

b) Do you see the significance here??

i) Let’s grant that there might be a bias reflecting through this chart vis-à-vis the wisdom of past management allocation of IBM financial resources.

ii) Even allowing for a “bias factor” (which may not exist), doesn’t this graph suggest that IBM has been propping up its Earnings Per Share…Revenues Per Share…(and all other metrics calculated by reference to total shares outstanding) through shrinking its stock float each year?

iii) All of this is executed under the laudatory banner of “Returning Value to Shareholders”…

iv) And yet simultaneously, it is an admission by management that during these years, it could not find any productive corporate use (acquisitions, new start-up enterprises, etc.) for those funds that was more profitable than buying back its own shares… even when the share price was (in no way) “depressed”.

c) What is the mid to long-range impact of share buybacks (beyond the initial “kick” for investors of “returned value”)?

i) It makes it easier for management to qualify for executive stock options/bonuses.

ii) It makes investors who only look at “EPS growth” more willing to buy IBM.

iii) It tends to result in positive press reviews/attitudes.

d) But, has it helped grow the company’s intrinsic value as an ongoing production/service/sales organization?

i) It certainly has not kept pace with CPI!

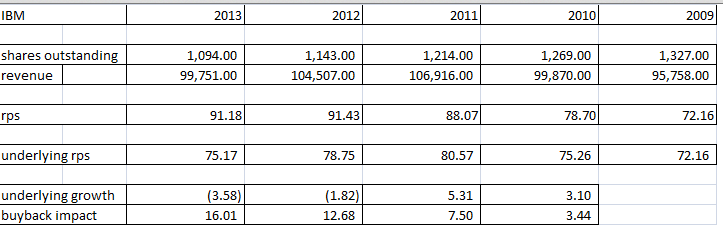

Let’s look at these questions a bit differently. Ravi Bala has done creative and extremely helpful work (also appearing in SeeekingAlpha.com) in identifying the degree to which this massive ongoing stock buyback effort has “masked” a relative paucity of organic growth. Bala prepared analyses for both EPS and Revenue Per Share (RPS) … with the gist of the spreadsheets being similar. So let’s review just the revenue side for now.

Bala calculated the RPS for the years 2009 (far right) to 2013 (far left). On line 6 he divided that year’s revenue by the number of shares outstanding that year. On line 8 he calculated the RPS figure on the assumption that no buybacks has taken place… that is he divided each year’s revenue by the number of shares outstanding in 2009!

The result is that we can see the cumulative impact on revenue of the buybacks. As you can see, there was RPS growth on an absolute basis in 2011. For 2012 and 2013, there was a reduction in RPS on an absolute basis… but an even larger reduction if you remove the accretive impact on RPS of the accumulated buybacks from prior years.

Over the intermediate to longer term, share buybacks can “disguise” a number of important corporate symptoms. For this reason, as well as the comment earlier regarding share buybacks being management’s admission that they are at a loss regarding any more profitable use of limited financial resources than buying company stock, that the term “Financial Engineering” has been attached to managements that chronically execute share buybacks.[6]

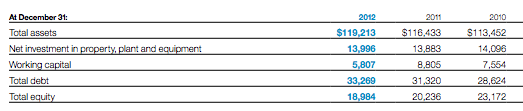

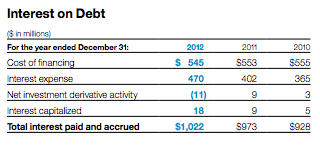

As a postscript related to share buybacks, they have also contributed to an increase in long-term debt and annual interest expense (to service the debt).

Clearly, IBM is going through a major transitional period! The truth is that Ms. Rometty has not put her last challenging quarterly earnings conference behind her. Inevitably, more pain lies ahead. History shows that IBM has “remade itself” twice before (in prior decades). However, those prior transitions took place in days when IBM was smaller and the pace of technological change was much slower! Today is a far different day and IBM is a far different, more complex company! I actively feel badly that she is now “reaping the whirlwind” that was sown by her predecessors!

I do have to give considerable credit, however, to Mr. Palmisano for his keen ability to interpret financial statements, graphs, and corporate trends! Take a close look at the graph showing the market value of IBM between 1985 and 2014. Now focus on the period that would represent December of 2011. That was the month Palmisano decided to retire from IBM.

Do you agree with me that the end of 2011 was a highpoint in the recent, contemporary history of IBM? At a bare minimum, market value was at a high, the great Oracle of Omaha had revealed his huge stake in IBM, and (in general) the press treated Palmisano with plaudits and praise. What a way to “go out at the top”.

INVESTOR TAKEAWAY:

What are the virtues of investing in IBM today? That is a question which would serve well as the investment world’s equivalent of a Rorschach Test! The answer may say more about the one who answers than about IBM itself!

I suspect Warren Buffett may still believe in the long-term value of the IBM brand. I know that Mr. Buffett is a cool customer – not prone to impulsive decisions of any short-term nature. So for now, he is still holding his shares. But I suspect that he’ll be looking over Ms. Rometty’s shoulder, looking for signs for a workable, credible, well-executed plan for the future.

It will be interesting to see what changes come to the Market Vectors Wide Moat ETF at the December 17th re-balancing. IBM is currently one of its 21 stock positions – based on its wide moat and its relative value vis-à-vis its sustainable profitability. IBM is certainly not currently “over valued” (having fallen over 18% from its 2014 high). However, I am confident that the Morningstar analysts who meet twice a week to review portfolio holdings, discuss/debate the “moats” of various proposed candidate stock holdings, and discern which companies demonstrate the “greatest value in generating excess profit within a sustainable business model” will be discussing IBM quite frequently (perhaps heatedly).

As for all of those “Baby Boomers” who (like me) vividly recall the day when IBM was “the” computer company… and one of the “bluest of Blue Chips” (after all, IBM was nicknamed “Big Blue”) – those days are gone. The “core” business of IBM, the operations that made it practically a nickname of “computer” (desktops, laptops, etc.) has long ago been sold off (Lenovo). And I must confess that I do not know what IBM’s “core business” is these days.

However, I will echo the description applied to IBM by Seeking Alpha writer, “Early Retiree”:

Despite the fact that IBM will continue paying out a dividend yielding (now) 2.7%… and the fact that it is in the venerable Dow Jones Index…

1) IBM is no longer a growth company;

2) It is (at least not for a while) a steady “blue chip”;

3) It is not even a slowly growing cash cow (although it does generate mega free cash flow).

At any rate, based on its currently ravages technical, you’ll likely have an extended period of time during which IBM will sit in a range in the mid-160’s (or lower) before it tries to mount a sustainable up move!

FOOTNOTES:

[1] That last one is my personal most-used standby.

[2] The use of the term “Blue Chip” springs from poker betting… assuming one uses the standard, simple set of chips that range from white chips (least valuable) to red chips (higher) to blue chips (the most valuable) [often white=$1, red=$5, blue=$25). Tradition (per Dow Jones news) holds that the first to utter the term was Oliver Gingold (of Dow Jones) sometime in 1923 or 1924. Apparently Gingold was standing by the stock ticker at a brokerage house that later became Merrill Lynch when he noticed several trades at $200 or $250 a share or more. The “lore” claims that he turned to Lucien Hooper of W.E. Hutton & Co. and said he intended to return to the office to “write about these blue-chip stocks”. He was obviously referring to stocks with high prices; but the term has come to be used to refer to quality stocks.

[3] Profits that exceed, to the greatest degree possible, the company’s cost of capital.

[4] To be fair to IBM management, it had benefited for years from a boost to earnings because of a weak U.S. Dollar. This year, the effect has reversed… hurting company financial metrics.

[5] My personal view is that Palmisano was foolish to make promises that big – especially since he had just struggled with the company through the very rough patch of the Financial Crisis…. followed by virtually unprecedented, unimagined monetary easing by the Federal Reserve. What part of “you can’t predict the future” didn’t he understand from that? I feel badly that Rometty had to eat Palmisano’s “crow”. Wall Street hates being “promised” something… and then having the promise violated!

[6] Yes, the term is used pejoratively!

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

If You'd Invested $1,000 in Shopify Stock 10 Years Ago, Here's How Much You'd Have Today

If You'd Invested $1,000 in Shopify Stock 10 Years Ago, Here's How Much You'd Have Today