In our two previous articles, we have reviewed the history of central banking in the United States — with a special focus directed at the impact upon the Federal Reserve System of the suspension of the “Gold Standard” during the “Great Depression”, and the war debt accumulated because of World War II and the Korean War. The pressure placed upon federal fiscal policy by that huge war debt led to a public confrontation between the Truman Administration and Federal Reserve leaders, the result of which cemented Federal Reserve independence. Finally, we critiqued the current Federal Reserve Board with regard to specific criteria

Despite the fact that Fed Chair Yellen, her predecessor (Ben Bernanke), and her current Fed colleagues are such frequent targets of criticism and second-guessing, there is no question that the responsibility of the Federal Reserve to manage U.S. monetary policy is extremely challenging. Specifically, their responsibility is to do the following:

Manage U.S. monetary policy in a manner that provides a maximized balance among employment, prices, and interest rates[1].

Before I hand the reins of the Federal Reserve System over to you, I want to offer a brief retrospective (and analysis) of how several different Fed leaders managed that responsibility during an extraordinary period of economic and political transition that occurred between 1970 and 1988.

RETROSPECTIVE ON THE COMPLEXITY OF EFFECTIVE FED POLICY AND THE PSYCHOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS OF FED LEADERSHIP

[For most of what follows, I must credit Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer for their highly informative analysis of Fed policy (Choosing the Federal Reserve Chair: Lessons from History) that was published in the Winter 2004 edition of the Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 18, Number 1.]

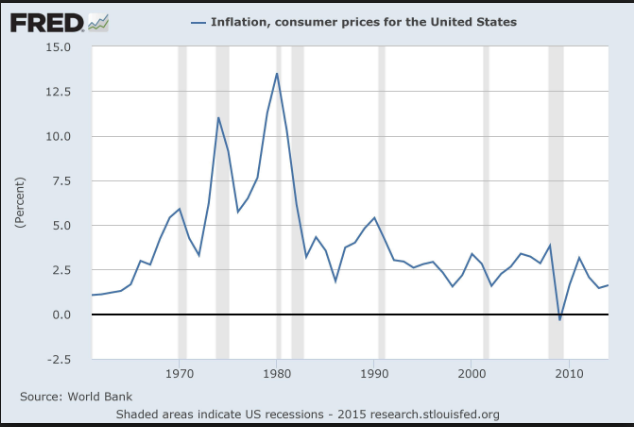

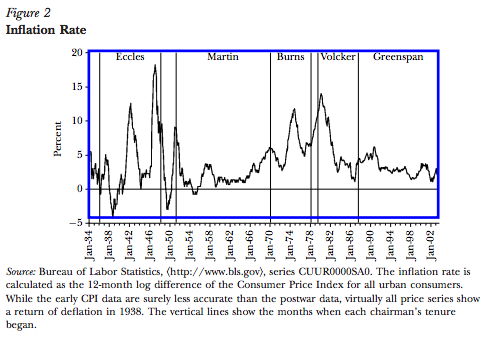

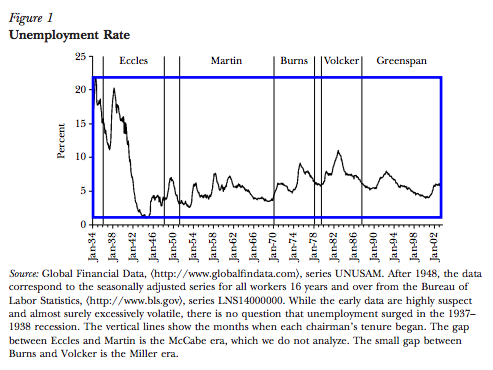

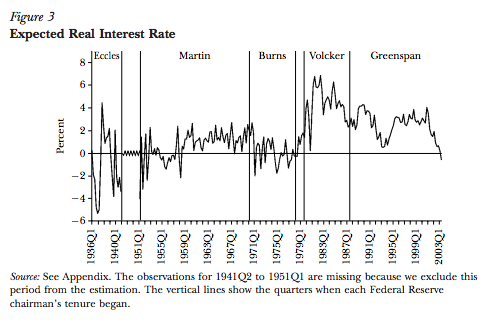

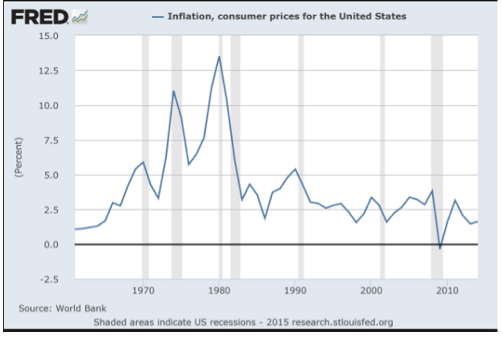

After a long period of “relative” stability with regard to inflation and unemployment during the period of William McChesney Martin as Fed Chair, the 1970’s ushered in the beginning of a period of much more variable economic metrics. To illustrate, take a good look at the following graphs:

Fed Chair Arthur Burns was widely recognized as a brilliant financial professional. However, his term as Fed Chair came at a time of significant economic transition within the U.S. economy. Unfortunately for Mr. Burns, the prevailing monetary philosophy/policy that worked under Mr. Martin’s long term in office began to “fail” during the term of Mr. Burns.

During Martin’s era, policy-makers believed that the “natural rate” of unemployment was quite low (perhaps in the 3-4% area). Any level above the “natural rate” would indicate some “slack” in the economy … slack that would tend to keep inflation low. In February of 1970, unemployment had risen toward 4%, and Burns reported to Congress:

“[w]e must now have the patience to wait for the improvement in price performance that will eventually result.” [He was referring to waiting for inflation to decrease.]

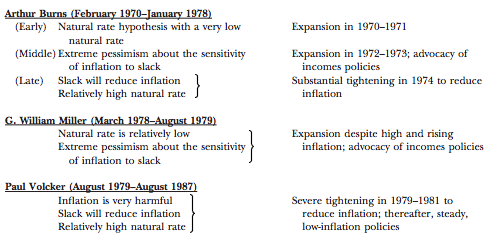

Because of the prevailing view shared by Fed members that there was “slack” in the economy, the Fed’s policy in those early months of Burns leadership was “expansionary” (or per Yellenspeak, “accommodative”).

By August of 1970, unemployment had moved higher to 5%, so Fed minutes revealed: “expectations of continuing inflation had abated considerably.” As a result, the Fed approved more monetary easing because they felt that such easing could be “sufficiently stimulative to foster moderate growth in real economic activity, but not… risk a resurgence of inflationary expectations.”

By July of 1971, one can tell that Mr. Burns was frustrated and a bit confounded. Here is an excerpt from his testimony to Congress (pay particular attention to the sentence I show in bold font]:

“A year or two ago it was generally expected that extensive slack in resource use, such as we have been experiencing, would lead to significant moderation in the inflationary spiral. This has not happened, either here or abroad. The rules of economics are not working in quite the way they used to. Despite extensive unemployment in our country, wage rate increases have not moderated. Despite much idle industrial capacity, commodity prices continue to rise rapidly. And the experience of other industrial countries… shouts warnings that even a long stretch of high and rising unemployment may not suffice to check the inflationary process.”

Around that same time, Burns opined that the rise of public sector unions, the impact of that rise on the labor movement in general, welfare and other factors might be responsible for the change[2]. Burns concluded that “monetary policy could do very little to arrest an inflation that rested so heavily on wage-cost pressures.”

The result was that Burns and a majority within the FOMC began to advocate wage and price guidelines, as well as a few other unconventional measures intended to reverse inflationary expectations more directly. However (in his defense) since the economic mechanisms that were commonly accepted at the time were not working, Burns was convinced that another course (however unpleasant) was required. However, wage/price controls (highly unpopular) only worked for a brief time, leaving Burns and the Fed with the task of developing a new approach.

In October of 1973, a new and transformative economic shock reared its head – the OPEC Oil Embargo – a form of economic punishment of the United States by the Arab oil powers for the U.S. support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War. What resulted was an exponential jump in global oil prices from $3/barrel to over $12/barrel – with U.S. prices climbing even higher.

As one can easily imagine, the task of Mr. Burns and the Fed became ever so more challenging. Just review the earlier inflation graph to see the steady rise of inflation following the start of that embargo!

So to all too briefly summarize the remainder of Burns’ term as Fed Chair, the Fed began to modify their understanding of the “natural rate” of unemployment… raising it significantly. This gave the Fed more leeway to “tighten” monetary policy in an effort to better manage inflation. As a result, the Burns’ Fed tightened policy substantially from 1974 until 1977, with some success (the earlier graph suggests that inflation headed back down toward 5.5% once the shock of the oil crisis waned).

By early 1977, with Burns sharing our human propensity for approval and success, he began to ease monetary policy in the hopes of securing reappointment as Fed Chair[3]. However, that attempt was unsuccessful; President Carter declined to re-nominate Burns as Chair.

G. William Miller followed Arthur Burns as Fed Chair … but only briefly, since he was soon appointed to serve as U.S. Treasury Secretary.

By March of 1978, Carter’s new nominee, G. William Miller, became chair. It is not surprising that, given his nomination by the President during the middle of his first term in office (and already focusing upon reelection) that Mr. Miller began his leadership of the Fed with a much lower understanding of the “natural rate” of employment (meaning that he felt that unemployment could go below 5.9% without any need for concern by the Fed regarding “low” unemployment putting pressure upon prices. As was pointed out earlier, the Burns’ Fed operated with a belief that the “natural rate” was higher than 5.9%). In addition, Miller did not have strong confidence regarding the sensitivity of inflation to slack in either employment or the economy.

As a result, the Miller Fed engaged in “expansionary” (aka “accommodative”) monetary policy despite rising inflation. Then, in mid 1979, Carter needed a new Treasury Secretary… so he chose to appoint Mr. Miller. Concurrently, to fill the vacancy at the Fed left by Miller’s move to Treasury… in August of 1979, the president nominated Paul Volcker to become Chair of the Federal Reserve.

In a classic case of bad timing, within three months of Mr. Volcker’s start as Chair of the Fed, widespread public discontent (and turbulent protests) in Iran began to come to a head – as 37,000 workers from Iran’s nationalized oil refineries slowed production from 6 million barrels/day down to just 1.5 million barrels/day! Soon countless foreign workers (including skilled oil workers) fled the country. Then on January 16, 1979, the Shah of Iran and his family fled the country, opening the way for the Ayatollah Khomeini to assume leadership. (Soon, matters would become further complicated when Iranians toppled the U.S. Embassy and took hostages.)

Paul Volcker served as Fed Chair during a period of extraordinarily high inflation. He became renowned for his handling of that challenge.

As we know, markets detest uncertainty. Therefore, oil prices escalated by over 100%, precipitating the “1979 (aka “Second”) Oil Crisis. To be specific, oil was priced at $15.85 in early April of 1979… but jumped to over $39.50[4] within the following 12-month period.

So the unfortunate, but extremely capable, Paul Volcker was faced with the not only counteracting the relatively high inflation bequeathed to him by Mr. Miller (during whose brief term inflation moved from about 8% to over 10%) … but also with the violent economic shock of a doubling in oil prices!

To no one’s surprise, fighting inflation became “Job One”! Here is just one quote that reflects Volcker’s ongoing war against inflation:

“We must not lose sight of the fundamental point that so many of the accumulated distortions and pressures in the economy can be traced to our high and stubborn inflation…. Progress on inflation is a prerequisite for . . . sustained, balanced growth”. (Bulletin, August 1981, pp. 613, 616).

Reflecting Volcker’s conviction that the primary method of inflation control/reduction had to be restraints placed upon aggregate demand, here is Volcker speaking in February of 1980:

“Monetary policy—restraint on growth of money and credit—is only effective over time; but experience shows that, with perseverance, it can and will be effective.”

With regard to employment, although it was an unpopular opinion, Volcker and most of his fellow Fed members adhered to a relatively high estimate of the “natural rate” – meaning that, in their view, the level of unemployment needed to reduce inflation was substantial. As an illustration of this, in March of 1980, with unemployment projected to rise above 8 percent, FOMC minutes indicate that

“the underlying inflation rate would not be reduced very much in the short run by the rather moderate contraction in activity generally being projected”. To translate that, they felt that 8% unemployment would not have much impact upon lowering inflation in the short run.

The result of this consensus within the FOMC regarding how to manage monetary policy during that challenging period of 1979 to 1987 was this:

An extremely contractionary monetary policy.

That policy conviction was so firm that their policy stayed the course through (and despite of) a severe recession.

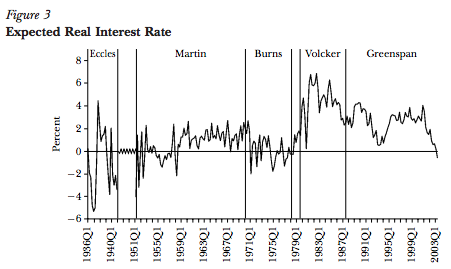

Note how high Volcker let real interest rates and unemployment move in order to curb the out-of-control rate of inflation:

In 1980, Volcker summarized the reason for his steadfast adherence to what many folks considered to be a cruel monetary stance (vis-à-vis unemployment):

“In the past, at critical junctures for economic stabilization policy, we have usually been more preoccupied with the possibility of near-term weakness in economic activity or other objectives than with the implications of our actions for future inflation. . . . The result has been our now chronic inflationary problem…. The broad objective of policy must be to break that ominous pattern. . . . Success will require that policy be consistently and persistently oriented to that end. Vacillation and procrastination, out of fears of recession or otherwise, would run grave risks.”

When the time came for a shift in Fed leadership, I clearly remember the great wringing of hands and gnawing of teeth that “the Markets” experienced at the prospect of losing Volcker as Fed Chair. Like him or not, he proved to be very dependable, steady, and articulate.

Alan Greenspan, perhaps the most colorful of all U.S. Federal Reserve Chairs. He earned the trust of Wall Street during and after “Black Monday” in October of 1987.

Alan Greenspan, in contrast, was relatively unknown and unproven. However, when Greenspan took the reigns of the Fed in August of 1987, not only did the world not end… but he even proved to be an able “Market Whisperer” during and after the scary event we remember as “Black Monday” (October 19, 1987)… during which global markets crashed, with the S&P 500 Index itself dropping over 22.5% in a single day!

Greenspan went on to a long run as Fed Chair… falling just 4 months short of eclipsing Martin’s record for Fed longevity. He became revered in many corners of Wall Street[5], and proved to be an easy target for comics who poked fun at his enigmatic communication style. It was Greenspan’s ability to engage in self-deprecating humor that endeared him to even those who may not have approved of his policy decisions, including this particular quote:

“I guess I should warn you, if I turn out to be particularly clear, you've probably misunderstood what I've said.”

NOW IMAGINE THAT YOU ARE THE CHAIR OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE

Through the power vested in me by MarketTamer.com, I pronounce you “Virtual Chair” of the Federal Reserve Bank![6] Now you have the responsibility of managing monetary policy in our globally interconnected world!

If you are willing to “hire” me as a staff person attached to your office, please allow me to help provide you with some background information that may help to inform your decision-making as we move forward.

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP):

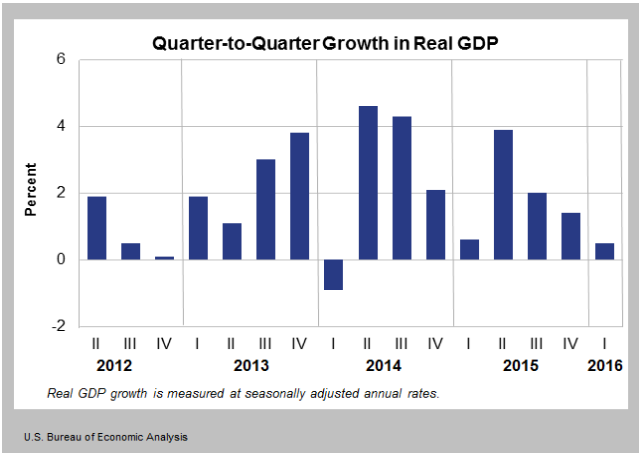

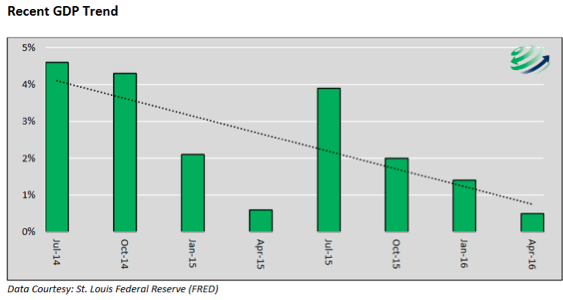

As the Chair knows quite well, the recent report regarding First Quarter 2016 GDP reflected modest growth of +0.5% (that is a Quarter-over-Quarter change, translated into an annualized figure). The Chair may want to share with the FOMC that 1Q growth, when compared to the previous 100 quarters (dating back to 1Q of 1991), places 86th from the top (or 15th from the bottom)[7]! That is hardly inspiring growth.

Placing this in more recent perspective, we can see that the past 6 months is running at an annualized growth rate of under 1.00%. The graph below (based on data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank (FRED), shows the trend of GDP since July of 2014:[8]

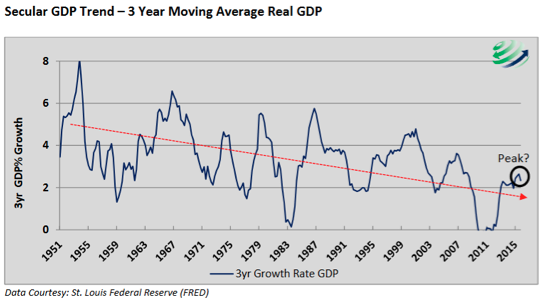

If we review a much longer period of time (back to 1951) we can view the “Big Picture” trend in GDP Growth through this graph (found at the same website):

This graph of the “Three-Year Moving Average of Real GDP” reveals that, when considering the most recent seven economic cycles, five of those have peaked at levels that are progressively lower. Moving to even finer detail, if one is so bold as to mathematically calculate the average growth decline from high to low within each cycle, one finds that the smallest decline was 3.0%. Given that, if we assume (equally boldly) that growth peaked (for this cycle) in 2015, the unfortunate implication is that (looking ahead) the prospective three-year average of growth will fall below 0%[9] (-0.7%). [Note: These figures are offered by way of a “worst case scenario. The assumptions are, as we indicated, quite “bold”!]

Review the “trend” in U.S. GDP between January 2014 and now. Doesn't it appear to have a downward bias?

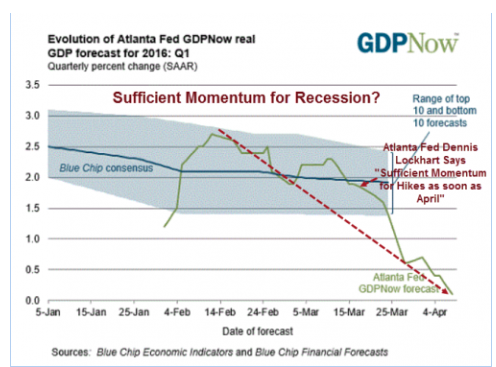

The following graph from the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank (it shows their relatively new “GDP Now” data matrix) suggests the perils of forward-looking economic projections:

Looking at this graph, we can see that in mid-February, the GDP Now projected 1Q growth at 2.7%!! Not long afterwards, Atlanta Fed President (Dennis Lockhart) suggested there was “sufficient momentum for hikes as soon as April”. However, as we can clearly see, the GDP Now projections kept falling (somewhat like a rock off a cliff). From such surprising developments comes the occasional need for a Fed official to remove “egg from his (or her) face.”

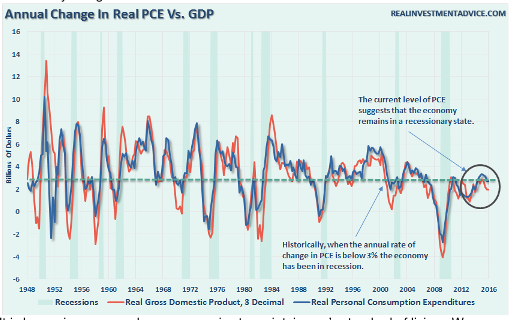

We know the U.S. consumer is central to the growth of U.S. GDP. Review this graph that relates the annual change in “Real Personal Consumption Expenditures” to U.S. GDP.

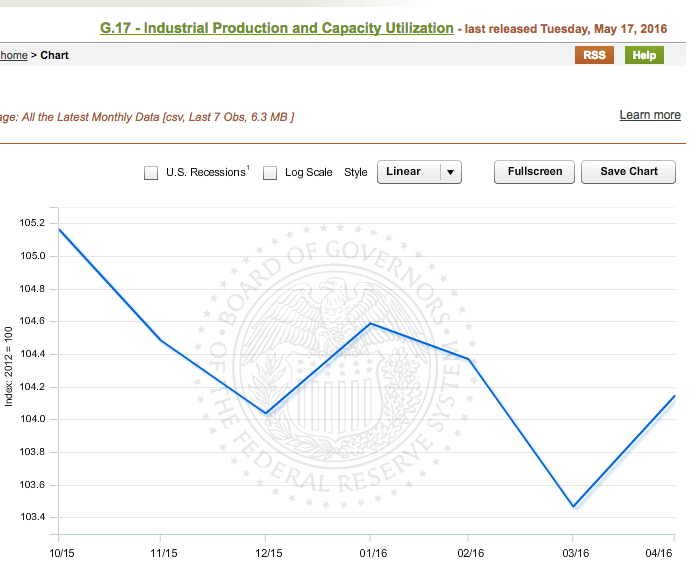

Admitting that no one graph can serve as a comprehensive ”tell” regarding national GDP, when we look at the next graph (from the Fed) of “U.S. Industrial Production & Capacity Utilization” (past 6 months), it should not be a surprise that the U.S. economy does not reflect great growth:

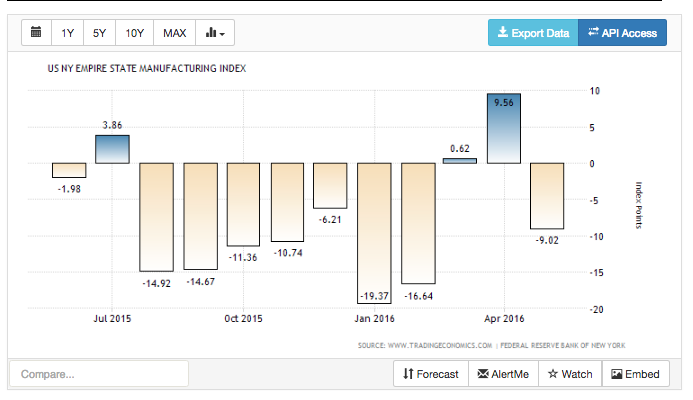

If in addition, we throw in the “Empire State Manufacturing Index” as a bonus, our less than stellar picture is confirmed. In fact, most of these graphs have been plateauing or trending downward:

Finally, it must be highlighted that our current period of U.S. economic expansion has become the second longest such period in over 65 years!! It is also the fourth longest U.S. expansion ever! The unfortunate implication from these statistics is that our expansion is “long in the tooth”. At some point (no one knows when) a recession will follow!!

EMPLOYMENT:

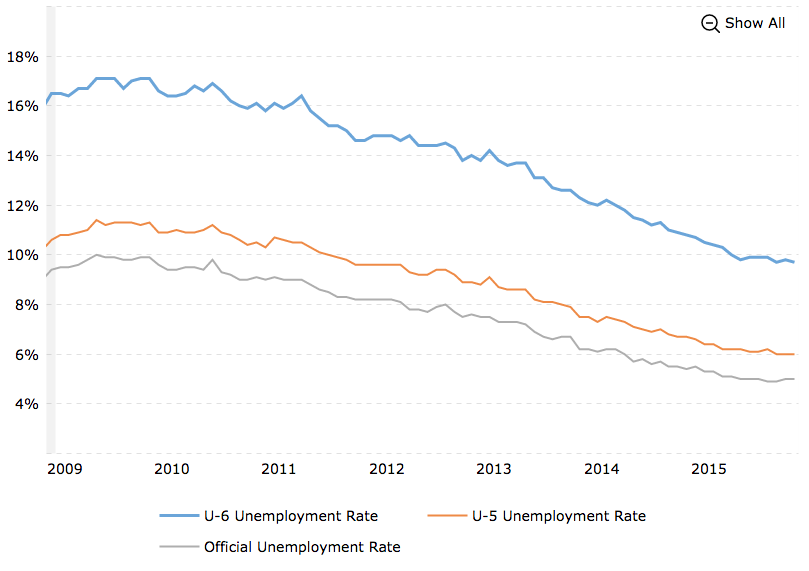

The Chair is aware that U.S. employment has experienced a slow but quite steady recovery from peak unemployment in 2010.

Here are a few of the most common ways of looking at U.S. employment:

U3 is the official unemployment rate.

U5 includes discouraged workers and all other marginally attached workers.

U6 adds on those workers who are part-time purely for economic reasons.

Peak 17.1% in Oct 2009 and Spring 2010

Currently, these data points rest at the following level:

U3 5.0%

U5 6.0%

U6 9.7%

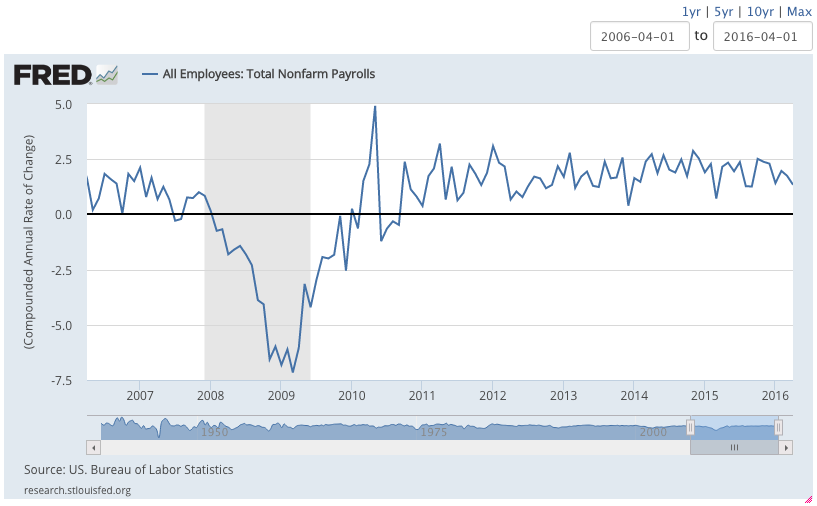

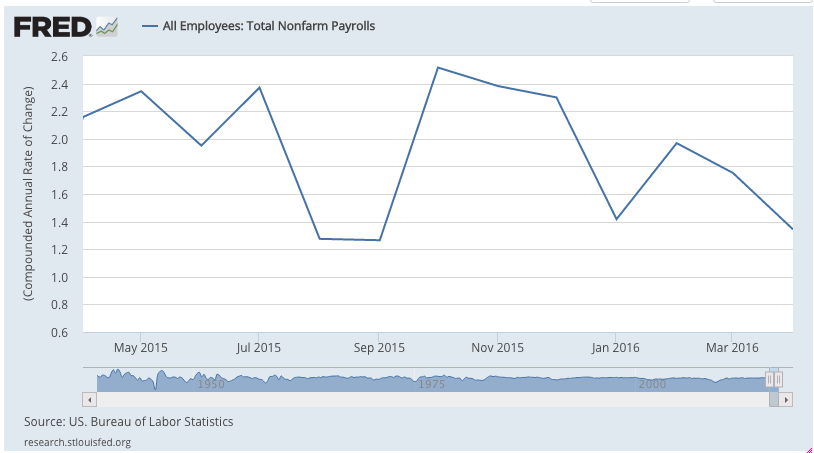

Compounded Annual Rate of Change in Non-Farm Payroll

May of 2010 saw the PEAK in the annual “Rate of Change” in employment growth.

During the past 12 months, the annual “Rate of Change” in employment growth has been trending stable to downward.

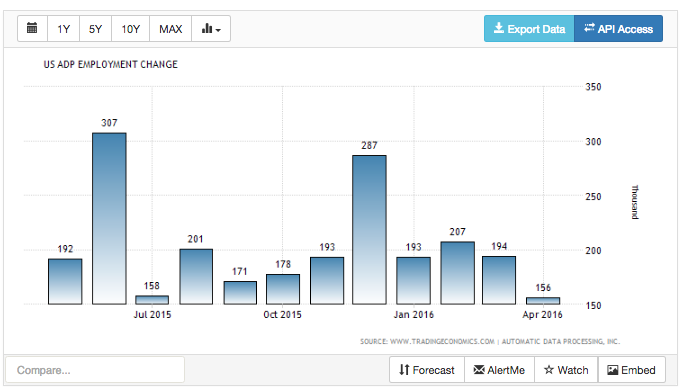

As you know, the “ADP Employment Change Report” (prior 12 months) is not an official government report. However, as an ongoing private sector gauge of U.S. employment, it is worthy of attention. Here is the latest graph:

Unfortunately, it offers a discouraging picture of employment.

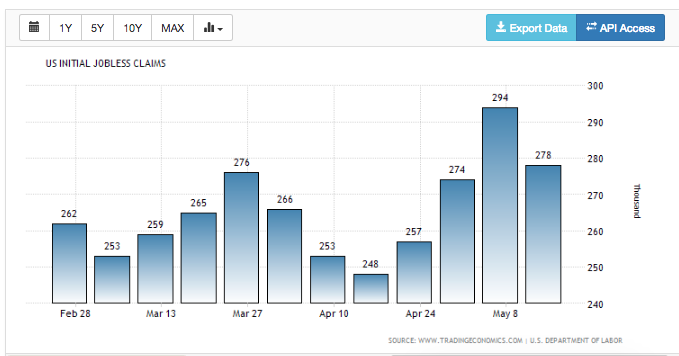

Recall that we have been seeing a lot of graphs that are either stable or trending downward. But here Is a graph that is trending upward:

Oooops! That is a graph of “Initial Jobless Claims” (from the Dept. of Labor). We don’t want that graph to trend upward! Sorry.

To all of the above, we must add a reminder that the precise set of definitions and assumptions regarding “Employment” used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is revised on a regular basis – beyond just the normal “Seasonal Adjustments”. That is not unlike the regular modifications made in the calculation of metrics such as the “Consumer Price Index” (CPI). However, even though such methodological adjustments are quite accepted within the academic setting, when government entities engage in such adjustments, the frequent suspicion is that the adjustments are carried out for political reasons.

As one simple case in point, quite a few analysts note that, on average, “jobs” in 2016 include a higher percentage of relatively low paying jobs … compared with the average job during the 2000-2009 period. Of course, this issue is a relatively moot one for members within the FOMC, since the only official figures at hand for FOMC work are those from the BLS.

INFLATION:

As the Chair knows, on an historical basis, the normal challenge for the Fed has been to keep inflation in check. That was certainly the challenge that perplexed Chairman Burns and Chairman Miller in the 1970’s, and the challenge that Chairman Volcker was finally able to overcome in the 1980’s.

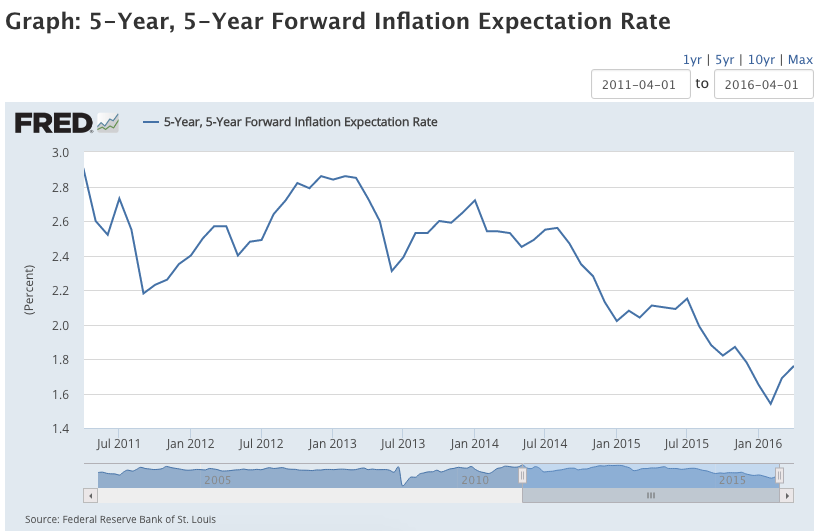

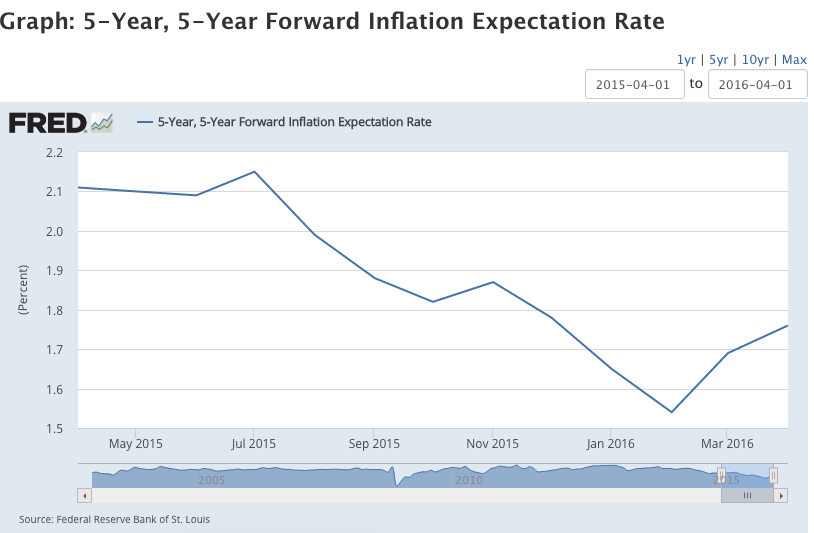

However, since the ravages of the Financial Crisis … with its accompanying severe economic dislocations and prolonged period of low or no economic growth… the specter of “Disinflation” has reared its ugly head. Therefore, the Fed and other world banks have actually been trying to “ignite” inflation – without great success.

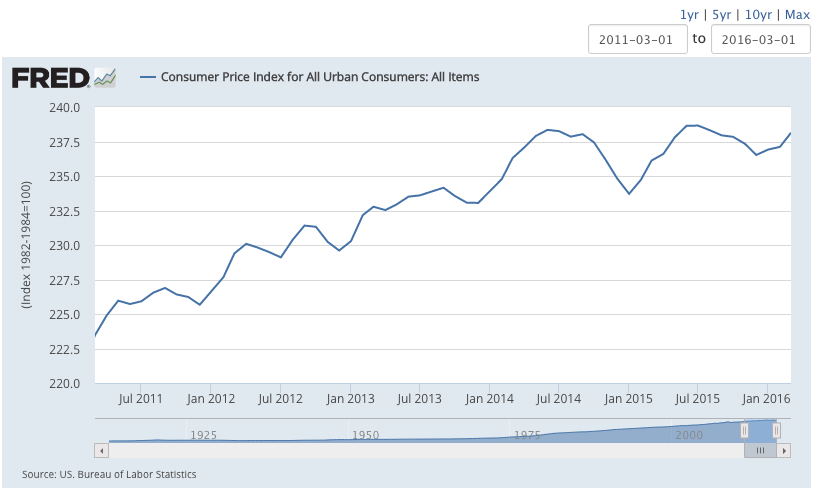

Below are two ways of looking at inflation:

1) On an absolute basis using CPI metrics;

2) On the basis of “expected future inflation”.

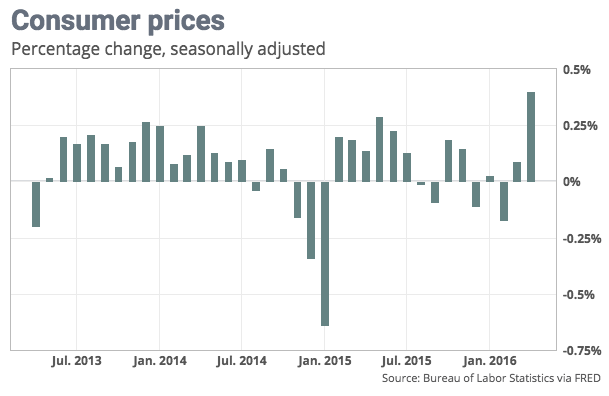

Before we move on, it must be added that on May 17th, the BLS reported the following:

U.S. prices for goods and services increased in April at the fastest pace in more than three years.

The CPI rose by a seasonally adjusted 0.4% in April … a jump of a magnitude not seen since February of 2013. led by the higher cost of gas and rent.

Over one half of the rise was due to gasoline prices; about one fourth of the increase was due to higher average rents.

However, although the stock market got spooked … falling almost 1%… and although two regional Fed presidents (Dennis Lockhart and John Williams[10]) opined the same day that the Fed could raise rates in June… it must be pointed out that:

Over the past 12 months … CPI is a very tame 1.1% (up from 0.9% in March).

It is also interesting that Lockhart suggests that the possibility of “Brexit” [the June vote in England regarding whether to pull out of the European Union] will not impact the Fed’s decision-making. Now in decades long past, it was assumed that that Fed made monetary policy decisions based strictly on domestic trends and factors. However, that is no longer the case. Just consider these two isolated quotes from the February 2016 minutes of the Federal Reserve FOMC meeting, which only scratch the surface in terms of the extent to which global trends and concerns now inform the deliberations among Fed leaders:

“Global financial market conditions deteriorated sharply in January, as recent developments in Chinese financial markets and the further decrease in crude oil prices appeared to increase concerns about global economic growth.”

“In assessing the medium-term outlook, participants discussed the extent to which the recent turbulence in global financial markets might restrain U.S. economic activity.”

Therefore, once again with all due respect to the esteemed Mr. Lockhart, I think it is extremely naïve for anyone to discount in any way the potential ramifications of an exit from the EU by Great Britain.

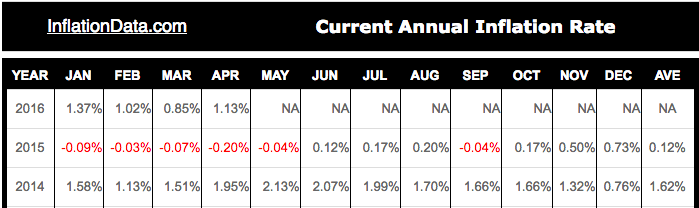

Finally, although not an official government table, these metrics from Inflation.com might be informative:

The chart reminds us of the variability of monthly metrics.

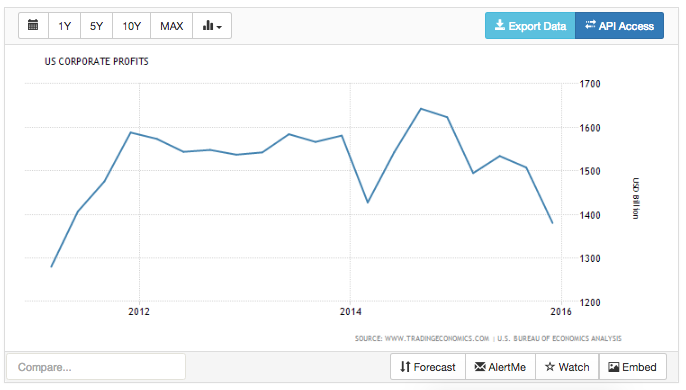

CORPORATE EARNINGS:

I confess to the Chair that “Corporate Earnings” are not a primary metric commonly associated with Fed monetary decisions. However, I know that you would agree to the stipulation that the trend of such earnings surely provides a significant indicator of economic strength. To that end, here is the latest Five-Year Chart of that metric[11]:

At the point at which most (over 90%) of S&P 500 companies had reported earnings for 2016 Q 1, total earnings were down by 7.2% on a Year-Over-Year (YoY) basis. In addition, those firms revealed an average drop in revenue of 1.4%.

In light of those metrics, the Chair might wonder why the stock market remains near all-time highs. Well, the Chair does not need reminding that Wall Street can be as quirky and irrational as cats. In the eyes of the market, because those reports were expected to have been worse, the results did not cause too much alarm.

Specifically, first quarter reports reflected the following:

1) 71.2% of corporate EPS surpassed analysts’ expectations;

2) 55.7% of company revenues beat those expectations.[12]

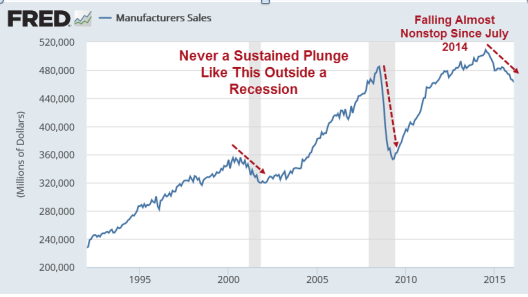

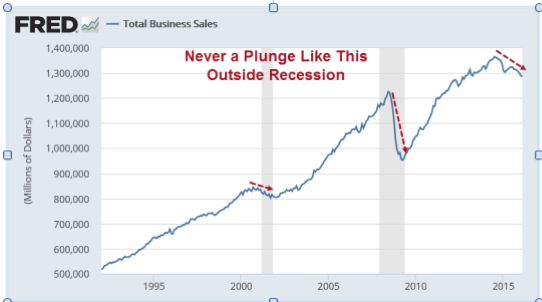

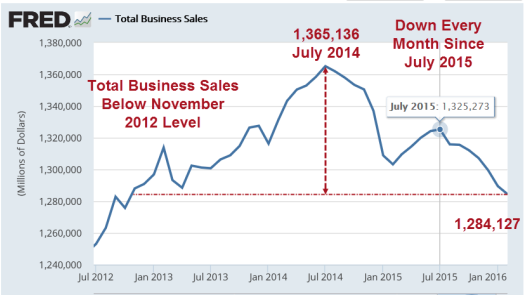

OTHER BUSINESS-RELATED CHARTS:

As I confessed earlier, business metrics are not as primary to the Fed as are metrics directly tied to employment, inflation, and growth. However, as with corporate earnings, certain business centric metrics can offer suggestive insights regarding national economic vibrancy. To that end, here are a few charts from earlier in 2016, all of which comes from a Fed-related source:

WHAT IS THE CHAIR'S ASSESSMENT?

Well, the time has come for you, as Chair, to take a stand! What will you say at the next Fed meeting… and especially, what will you say at the next Fed Press Conference?WHAT IS THE CHAIR’S ASSESSMENT?

We’ll all be behind you!![13]

INVESTOR TAKEAWAY:

I will bet that somewhere far beyond our purview, former Fed Chairs Burns, Miller, Volcker, and Greenspan are relieved that they did not face a national and global environment such as we face today!

The fact is that there has never been a global economic environment quite like we face today. As we demonstrated in an earlier article, many of the timeless indicators, strategies, and “truths” from decades gone by no longer “work” as effectively as they once did.

One reality that all investors must be mindful of at all times when listening to Bloomberg Radio or watching CNBC or Fox Business News is the following:

Whenever a so-called “expert” opines upon what is or is not currently a “good” investment, never ever accept their opinion at face value! It is absolutely essential to know what the background and “self-interest” is of each such “expert” before we can accurately assess the value of any given opinion!

As a ridiculous example, would we take merely at face value a statement on CNBC by Apple (AAPL) CEO Tim Cook that investors should buy AAPL now because it is significantly undervalued? Of course not! He most definitely is not an objective observer on the subject of AAPL stock!

In a similar fashion, the published opinion of an analyst from a major investment bank appeared on May 18th … to the effect that Tesla (TSLA) is undervalued… and that his rating on the stock has been raised (to “Buy” from “Hold”[14]). In addition, the “target price” was raised up to $250. The commentary included the following:

“While we believe [Tesla’s] volume targets are ambitious, Street and investor expectations seem more grounded and following a 23% decline in the share price post the Model 3 unveil, we do not believe Tesla shares are fully capturing the company’s disruptive potential,”

Isn’t it fascinating then, that just a couple of days later it was reported that TSLA is “coming to the market” with a $2 billion offering … to secure more capital for its ongoing expansion. Take a guess which investment bank was announced as the “underwriter” of that offering.

Yes… exactly! The very same investment bank for whom the TSLA analyst works!! Of course (wink, wink) it was merely a coincidence!

This is just one illustration of why anyone from an investment bank may not be considered an entirely objective source of investment advice regarding such matters!

Related to the above thought, it is my humble opinion that much of what is passed off within the investment world as “expert advice” is, more accurately, advice that reflects what I call the “Mirror of Erised Effect”.

For those few among you whom are puzzled by that to which I refer, the “Mirror of Erised” is a part of the infamous “Harry Potter” saga. As explained in the series by the iconic (and towering) figure of Albus Dumbledore:

The Mirror of Erised is a mirror that reveals the “deepest, most desperate desire of our hearts”.

In fact, I am sure you noticed that “Erised” is “DESIRE” spelled backwards… just as it would appear if reflected in a mirror!

If you vision is particularly acute, you may detect words engraved on the frame of the mirror:

“Erised stra ehru oyt ube cafru oyt on wohsi”

Of course, that writing means (when you reverse the order):

“I show not your face but your heart’s desire”

Therefore, one can fairly posit thoughts such as the following:

A stockbroker is likely to “see” that stocks are fairly or undervalued.

A bond dealer is likely to “see” that bonds are a better investment than stocks at elevated equity valuation levels.

A case in point regarding the above … paraphrased to the best of my ability… could be heard on financial radio today (the 18th of May):

Responding to the common perception that stocks are (at best) “fairly valued”… and at worst “over valued”, one stock broker said that currently, comparing stock yields versus bond yields reveals that “stocks are more attractive than bonds” to a greater extend than was the case between 2000 and 2008.

I can guarantee every investor that if I want to make a “case” for a certain investment, I can make it sound quite compelling if I emphasize certain elements to the exclusion of other elements! That is simply the essence of “salesmanship”.

The key for investors is to avoid being “taken in” by a sales person who uses “facts”, but still manages to distort reality as viewed more objectively.

Finally, allow me to offer two more thoughts for your consideration:

1) Who benefits the most within a low interest rate environment?

Consider these facts:

a) As of 4/30/16, the market capitalization of the U.S. stock market and the S&P 500, compared with the total U.S. national debt and the size of the U.S. economy is as follows (based upon data from BTN Research):

| DESCRIPTION | SIZE (in Trillions of U.S. Dollars) |

| U.S. Stock Market | 23.9 |

| S&P 500 Index | 18.9 |

| U.S. Economy | 18.2 |

| U.S. National Debt | 19.2 |

Are you surprised by any of these figures? Do they suggest anything?

b) In 1960, the U.S. national debt stood at 54% of the size of the U.S. economy.

As we see above, the current national debt stands at 105% of the size of the U.S. economy. (Source of data: The U.S. White House)

c) On 12/31/07, the average rate by the U.S. government on its debt was 4.838%).

As of 4/30/16, the average interest paid by the U.S. government on its debt was 2.322%. (Source of data: U.S. Treasury Department).

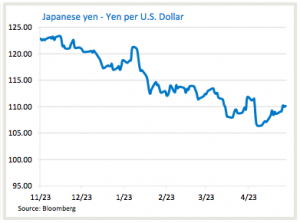

2) In light of the significantly heightened complexity of exchange rate issues (simply consider just the desire of Japanese Prime Minister (Shinzo Abe) to lower the value of the Yen versus the Dollar and the determination of the People’s Republic of China to more tightly manage the value of its currency)… not to mention the negative impact on U.S. corporate earnings when the U.S. Dollar zoomed upward between mid-2014 and March of 2015)… perhaps Fed members need to review the Noble Prize winning work of Robert A. Mundell.

He won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Economics for:

“for his analysis of monetary and fiscal policy under different exchange rate regimes and his analysis of optimum currency areas.”

Then, of course, in light of the challenge the Fed faces with regard to the “stabilization” of monetary policy, perhaps a review of Milton Friedman’s work is in order as well.

He won the 1976 Noble Prize for:

“his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy.”

ADDENDUM:

As a point of clarification, this article was written about one week prior to the release of the April Minutes of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee. With the news headlines trumpeting quotes from two Fed leaders that a June rate hike is “on the table”… I contemplated why the specter of an imminent rate hike might pop up now (particularly in light of all the data we have looked at).

First, let’s stipulate that reading the collective (much less individual) minds of these Fed leaders is a quixotic[15] endeavor! However, we all know that Japanese leaders want to devalue the Yen. Looking at the chart below, that means they would rather have the “Yen Per Dollar” increase…. back to at least where it was in November. Other G-7 leaders have warned Japan’s leaders not to engage in policies that devalue the Yen.

It is curious then that on May 20th (just after all the “Fedspeak” about a U.S. interest rate increase), this story appeared in the Wall Street Journal:

“Japanese Finance Minister Taro Aso on Friday reiterated his country’s commitment to refraining from competitive currency devaluation during a meeting of the Group of Seven finance ministers and central bank chiefs.

‘I told my fellow G-7 ministers that Japan is committed to refraining from competitive devaluation.’”

I admit this is a far-fetched idea, but consider the possibility of the Fed (secretly) promising a rate increase, which would tend to result in (but not guarantee) a lower value for the Yen … in an effort to help the Japanese. Of course, such a policy would be foolish, since the “collateral” effects of a rate increase would be unpredictable and potentially outweigh any benefit vis-à-vis the Yen. However, history has revealed more “off the wall” developments than that.

DISCLOSURE:

The author (obviously) finds the Fed and its history far too fascinating!! But at least he can take comfort in the fact that he no longer believes anything any Fed official says at any given time, nor anything any given “Fed expert” spews forth on TV… and absolutely never tries to “outguess the Fed” in his investment decisions!

The author does not hold a position in AAPL or TSLA.

Nothing in this article is intended as a recommendation to buy or sell anything. Always consult with your financial advisor regarding changes in your portfolio – either subtractions or additions.

FOOTNOTE:

[1] The original Federal Reserve Act legislation established three essential objectives of U.S. monetary policy: 1) maximizing employment, 2) stabilizing prices, and 3) moderating long-term interest rates. The first two of these are often referred to as the “dual mandate” of the Federal Reserve.

[2] Such is what he suggested in the minutes from the June 8, 1971 Federal Reserve Meeting.

[3] His term was up as of January 1978, so he would either be re-appointed or replaced.

[4] That turned out to be the “High” for oil prices until almost 30 years later, in March of 2008!

[5] And of course, reviled by others.

[6] To avoid embarrassment, please do not contact CNBC, Fox Business News, or Bloomberg TV offering an interview on the state of the economy and future interest rates!

[7] Those figures come from the Department of Commerce

[8] The graph is found at: http://realinvestmentadvice.com/odds-are-stacked-against-equity-investors

[9] Subtracting 3.0% from the current level of 2.3% yields an average three-year growth of -0.7%.

[10] With all due respect to Williams and Lockhart, neither one of them is a voting member of the FOMC. It strikes me that either they love to see themselves quoted in the press… or they enjoy taking the risk of hart(once again) being proven “wrong” [in the event the Fed chooses not to raise rates in June].

[11] From http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-states/corporate-profits

[12] All of this confirms what my daddy told me while I was growing up: “Son, remember that as you evaluate anything in life, it all depends upon what you compare it to!”

[13] Way behind you… since no matter what you say, everything from simple “barbs” to “slings and arrows” will be headed straight your way and we would prefer to not suffer collateral damage!

[14] Bloomberg Radio’s report said: “from Neutral/Neutral to Neutral/Buy”… But newspaper reports said from “Hold” to “Buy”. It is fascinating how similar Wall Street’s terminology is reminiscent to that of George Orwell’s 1984 …. at least in its ability to obfuscate.

[15] Meaning… it sounds possible, but is not practical.

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

3 No-Brainer EV Stocks to Buy With $100 Right Now

3 No-Brainer EV Stocks to Buy With $100 Right Now