In years long gone by, the financial markets were primarily moved by economic factors, including such things as:

1) Corporate Earnings;

2) Federal tax policy (eg. the lowering of capital gains tax on long-term appreciation; a special rate for “Qualified Dividend” income);

3) Announcement of major government contracts;

4) News regarding economic metrics (GDP growth; etc.)

Of course (as always) the markets were often “moved” as well by big traders, government intervention (visible or invisible), those who attempted manipulation (such as the Herbert and Nelson Hunt’s attempt to corner the silver market in 1980, and the federal government’s counter efforts[1]), etc. However, on a day-by-day basis, markets generally moved more reliably in accordance with economic fundamental than they have since the onset of the Financial Crisis!

In fact, the markets moved in patterns sufficiently reliable that most of the standard bag of fundamental and technical analysis “tools” proved very helpful to investors and traders through the decades.

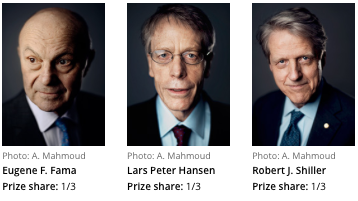

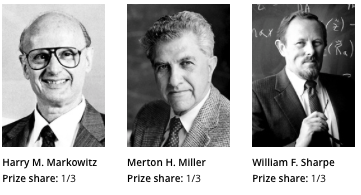

In addition, there was sufficient market consistency (ie. certain trends, patterns, etc. were “reliable”) to enable numerous Noble Prize[2] winning economists to develop market “models” that merited global acclaim, such as

2013: Eugene F. Fama; Lars Peter Hansen; Robert J. Shiller[3] — won the Noble Prize “for their empirical analysis of asset prices”.

1997: Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes[4] – won the Noble Prize “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives”

1990: Harry M. Markowitz[5]; Merton H. Miller; Wiliiam F. Sharpe[6] — “for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics”

1985: Franco Modigliani — “for his pioneering analyses of saving and of financial markets”

1981: James Tobin — “for his analysis of financial markets and their relations to expenditure decisions, employment, production and prices”

Alas, since the advent and global spread of “Quantitative Easing” – monetary stimulation on an unprecedented scale (and beyond anyone’s wildest dreams) – there have been chronic dislocations between economic fundamentals and market movements.

As a number of commentators have been pointing out for many months now, when compared with market action during most of the 20th Century, market behavior since at least 2010 has often seemed as though it comes straight out of an “Alice in Wonderland” world, within which:

Bad news is good news (because it fosters monetary support);

Good news is bad news (because too much of that will lead to higher interest rates).

Needless to say, many of the “rules”, “models”, “strategies”, etc. that accomplished portfolio managers and traders relied upon in decades gone by have not been “working” as they used to work. Therefore, it is not surprising that market commentary has frequently been peppered by comments such as “I’ve never seen this type of price action before”[7]

In light of all of this, and the ongoing (albeit questionable) reality that the most important “market maker” in our current era happens to be Janet Yellen and her Federal Reserve Bank colleagues, I thought it could prove to be enlightening to take a deeper look at this institution that used to lurk in the “background” of our economic and investment life, but has lately (for better or worse) captured “center stage”!

So let’s start off with a bit of Historical Federal Reserve Trivia [Correct Answers can be found in the Appendix]:

1) In what year was the Federal Reserve legislated into existence:

- a) 1935 (during the Great Depression)

- b) 1921 (following World War I)

- c) 1907 (due to the mid-October “Banker’s Panic”)

- d) 1913 (Woodrow Wilson felt that the gold standard made currency too tight)

2) Who was officially the first Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- a) William P.G. Harding

- b) Charles Sumner Hamlin

- c) Marriner S. Eccles

3) Which Federal Reserve Chair holds the record for the longest term in that office?

- a) Alan Greenpan

- b) Paul A. Volcker

- c) William M. Martin

- d) Arthur F. Burns

4) Which of the following statements was that of a Federal Reserve Chair?

- a) “The nation is prosperous on the whole, but how much prosperity is there in a hole?”

- b) “An economist's guess is liable to be as good as anybody else’s.”

- c) ”A perpetual deficit is the road to undermining any currency.”

5) Which of these statements came from a Federal Reserve Chair?

- a) “There is two things that can disrupt business in this country. One is War, and the other is a meeting of the Federal Reserve Bank.”

- b) “People know that inflation erodes the real value of the government's debt and, therefore, that it is in the interest of the government to create some inflation.”

- c) “The whole financial structure of Wall Street seems to rise or fall on the mere fact that the Federal Reserve Bank raises or lowers the amount of interest. Any business that can't survive a one percent change must be skating on thin ice. …. But you let Wall Street have a nightmare and the whole country has to help to get them back into bed again.”

6) Which statement was actually uttered by a Federal Reserve Chair?

- a) ”They don't really know what the money supply is now, even today. They print some figures — I'm not trying to make fun of it — but a lot of it is just almost superstition.”

- b) “Clearly, sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets. We can see that in the inverse relationship exhibited by price/earnings ratios and the rate of inflation in the past. But how do we know when irrational exuberancehas unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”

- c) “When I started my first job [in finance]… it was an article of faith in central banking that secrecy about monetary policy decisions was the best policy: Central banks, as a rule, did not discuss these decisions, let alone their future policy intentions.”

7) Which U.S. President became so frustrated by the Federal Reserve that he instructed all Fed Governors to attend a mediation meeting at the White House?

- a) Andrew Jackson

- b) Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- c) Richard Nixon

- d) Harry Truman

8) Which Central Bank is oldest:

- a) U.S. Federal Reserve Bank

- b) Bank of Japan (“Nichigin” for short)

- c) Bank of England

- d) Central Bank of Russia

- e) People’s Bank of China (PBC)

9) In which year was the oldest existing Central Bank founded?

- a) 1990

- b) 1913

- c) 1948

- d) 1882

- e) 1694

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE U.S. FEDERAL RESERVE BANK:

If one studies the history of banking in the United States, the clearest patterns that emerge are at least the following:

1) The immense cost of war was perhaps the strongest force that, upon several occasions, created the political will in the U.S. toward “central banking”;

2) At least through the first 100 years of U.S. history, if it had not been for the thorny issue of how to handle overwhelming war debts, the national preference was toward de-centralized banking.

3) However, that being stipulated, the fact is that, through the course of U.S. history, unregulated banks have frequently enabled less principled bankers to engage in activities that were personally very profitable… but clearly did not serve the “greater good” of the state and/or the country![8] Therefore, the regular emergence of unprincipled bankers and problematic banks were definitely an impetus toward government regulation.

4) In addition, the benefits of a currency that was accepted throughout all of the states that constituted the United States … to facilitate commerce, trade, and free movement throughout the nation… was another key factor at work within U.S. banking history.

Alexander Hamilton during his college years. IMAGE CREDIT: http://www.biography.com/people/alexander-hamilton-9326481#synopsis

With the Tony Award winning success of the Broadway musical “Hamilton”, many folks are becoming familiar with the financial genius of Alexander Hamilton – who was not only the first U.S. Treasury Secretary, but seemingly the only one with the insight and political acumen to overcome the following glaring issues that followed George Washington’s victory at Yorktown (concluding the Revolutionary War):

1) The former colonies had no common currency (many states printed their own);

2) Collectively, the nation and its many “states” had accumulated immense amounts of “war debts”.

Given the above, here is an oversimplified summary of Hamilton’s plan to resolve these issues:

- The Constitution prohibited states from issuing their own currency;

- The Bank of the United States was founded in 1790 (modeled upon the Bank of England);

- It issued national currency.

- The federal government assumed the accumulated war debts of the former colonies

- The Bank was intended to facilitate government finances by getting the new government functioning and executing a longer-range plan for the retirement of debt.

- The Bank also functioned as a commercial bank (before the war, the Bank of England had prohibited rival banks from starting in the colonies). Hamilton envisioned the Bank of the United States creating a central source of capital for loans to new businesses that could help to grow the young economy.

- The bank was based in Philadelphia – but had a branch in each of the new country’s eight largest cities.

Over the next couple of decades, the result of Hamilton’s efforts was as follows:

- The Bank of the United States paid off the country’s war debts.

- It grew strong as a commercial bank… with its commercial activities dwarfing its public activities.

However, when the war debts were retired, and with “politics” being “politics”… central bank critics began to emerge… charging that the Bank was unconstitutional (the Constitution granted the power to print money and to tax to the Congress, not to a commercial bank).

Therefore, the Bank’s charter was not renewed in 1811 (the renewal act failed by one vote!!). The Bank of the United States ceased operation.

Then a not so funny thing happened:

The United States got into another war – the War of 1812.

The consequences were quite predictable:

1) Federal debts rapidly mounted

2) Most state banks (many of which issued their own currency) suspended “specie payment” (ie. the exchange of paper currency for gold… which under the “gold standard” was the only thing that made paper money worth anything)

Suddenly, the U.S. public (and their politicians) began to see value in a “national bank”.

Congress chartered the “Second Bank of the United States” in 1816. This is what that Bank looked like:

1) Headquartered in Philadelphia, it eventually opened 29 branches in large cities across the nation;

2) It served to promote a uniform currency (including forcing state banks to resume “species payment”). Therefore it functioned as a clearinghouse – holding large amounts of other banks’ notes in reserve.

3) It also carried regulatory authority – it could discipline banks that over-issued notes.

Alas, the first president of the Second Bank was incompetent… and he almost led the bank into insolvency. But Langdon Cheves was rushed into leadership of the bank in order to save the bank – which he did successfully! Then Nicholas Biddle replaced Cheves in 1822. Both Cheves and Biddle managed bank operations quite effectively.

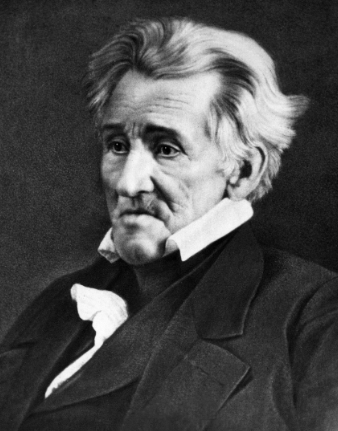

However, “politics” being “politics”, the political winds changed by 1828 … primarily due to the populist views of presidential candidate Andrew Jackson. Jackson was fearful of the vulnerabilities that became apparent during the horribly administered first two years of the Second Bank’s existence… and Jackson was extremely suspicious of bankers, believing they were susceptible to corruption, and therefore untrustworthy and in need of government control.

Jackson won the 1828 election. Although the bank was operating quite effectively at that point, Jackson remained suspicious. Then things took a turn for the worst:

- Jackson made his anti-national bank feelings publicly known.

- Bank president Biddle took exception and began to use bank resources against Jackson.

Jackson (never one known for controlled emotion) dug in his heels and became stronger in his opposition.

When the Second Bank charter came up for renewal, Jackson refused to approve it; in addition, Jackson pulled federal deposits from its vaults.

The Second Bank of the United States steadily withered away until its charter expired in 1836.

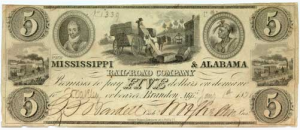

The following 16 years of U.S. history witnessed the “Free Banking Era… leading to the emergence of hundreds of new banks, most of which issued their own notes (currency). As that currency circulated around the growing nation, they often traded at a discount (varying in accordance with distance from the issuer and perceived issuer strength).

An interesting sidelight of the “Free Banking” period was the emergence of a private “quasi” central bank. After Jackson eliminated the Second Bank, a Boston bank (Suffolk Bank) began to fulfill many of the functions of a central bank (eg. clearing payments, exchanging notes and even disciplining banks that were over-issuing their notes)[9]. Later, a rapidly rising volume of note and check transactions in the New York area during the late 1840’s prompted the 1853 creation of the New York Clearinghouse Association. The Association proved to be an effective way for the city's banks to exchange notes and checks and settle accounts.

U.S. banking proceeded along this line until something significant changed. Can you guess what that was? [Hint: think about our earlier list of “patterns” related to central bank history.]

The beginning of the War Between the States (aka U.S. Civil War)

An exponential growth in federal debt and the need to finance that debt, as well as expand the government’s ability to secure additional debt, combined to “shift the political winds”. Interest in a national bank grew rapidly. But this time, the design of the new national bank system incorporated many of the features of the “Free Banking” era.

This new “national banking system” was established in 1863:

1) It allowed banks to choose between a national charter and a state charter.

a) National Charter banks were required to issue government–printed bills (instead of their own notes).

b) Those notes had to be backed by federal bonds, which helped fund the war effort.

2) In an impressive display of political sophistry, the legislation that created this national banking system paid much lip service to the pluses of maintaining the state chartered banks (largely “as is”).

a) One can easily imagine that various “states’ rights” advocates in Congress made that provision necessary.

b) But one can equally imagine that “central bank” advocates counted on getting rid of state charters once the pressure and turbulence of war had passed.

c) Not surprisingly then, in 1865, state bank notes were taxed out of existence!!

Here is the bottom line:

After almost 100 years of existence, the United States finally achieved the establishment of a truly uniform national currency!

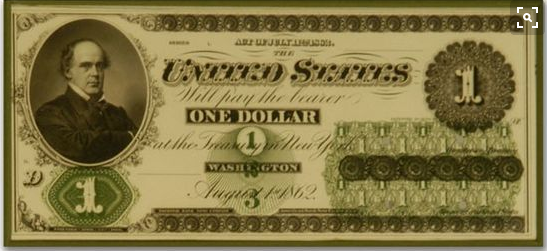

This is what the “original” one dollar U.S. dollar bill looked like … produced in the midst of the War Between the States.

One of the most vital functions of this national bank system in those early years was to serve as the promoter and distributor of the famous “War Bonds” that were introduced (at the prompting of President Lincoln and his administration) by U.S. financier (aka “banker”) Jay Cooke. Countless experts suggest that, without the abundance of the new money that Cooke’s “War Bonds” raked into the Federal Treasury, Lincoln could never have won the war.

But please do not think that Mr. Cooke deserves the description of “hero”! The plain truth is that Cooke became filthy rich as the result of his efforts. Cooke soon utilized his newly gathered fortune to finance railroads in the Northeast. History generally records Jay Cooke as the Cooke the “first” U.S. investment banker and the founder of the first U.S. wire house firm.[10]

Between 1863 and 1913, this national banking system produced many positives… but it fell victim (or rather, the banking public fell victim) to at least one “bank panic” in each decade following the Civil War.

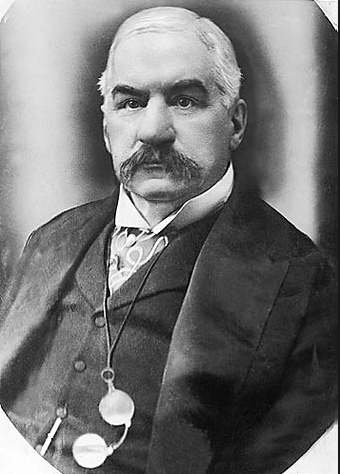

“The Panic of 1893” was especially destructive, coming as it did in the midst of the worst depression that the U.S. had (until then) ever suffered. Unfortunately, the economy only recovered after the intervention of banking mogul[11] J.P. Morgan. Much as was the case with Jay Cooke, Morgan (and his friends) made a sizable profit through his intervention.

Unfortunately, another such “Panic” occurred in 1907[12] and it resulted in a very painful recession. At that point, not even members of Congress and bankers are so uneducable that they couldn’t recognize the need for some form of change! The result was:

1) The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908, which:

a) Permitted national banks to start national currency associations[13] to issue emergency currency… backed by both government bonds and just about any securities held by the banks (yes, really![14])

b) In addition, a 5 percent tax was accessed on any such “emergency currency” for the first month it was “outstanding” and a 1 percent increase for the following months it was “outstanding”.[15]

c) Much more significantly, this Act created the “National Monetary Commission” – charged with proposing a long-term solution to the nation’s well-documented, chronic banking and finance issues

2) However, “politics” being “politics”, the 1912 election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson led to the scrapping of the Aldrich-Vreeland” process/plan. Wilson replaced that plan with a new plan designed by Congressman Carter Glass (VA) and Dr. H. Parker Willis (an Economics professor)[16]… which after a year of debate, compromise, and revision, became the Federal Reserve Act in December of 1913.

What were key aspects of this Glass/Willis central bank?

1) Glass and Willis removed any commercial lending functions from the bank (having learned the complications of commercial lending from “Second Bank” history) thereby ensuring that the bank would largely be a “public” institution.

2) Significantly, any revenue in excess of cost (ie. “profits”) were to be transferred into the U.S. Treasury.

3) The payments system in the U.S. was placed under the authority of the bank – with financial transfers and check processing that was formerly handled by private clearinghouses to begin being processed by the central bank… with related incoming fees to be designated for the covering of central bank operating expenses.

4) One of the major “political” aspects of the Glass/Willis design avoided much of what Andrew Jackson found offensive in the Second Bank:

a) The new bank was decentralized to curtail the aggregation of power;

b) The prime operational focus of the bank was to take place through 12 District Banks, operating independently. Each of those twelve banks:

i) Had it’s own president

ii) Issued it’s own money (backed by the promise of “species payment” … ie. redemption in gold).

c) To hold this decentralized system together, an oversight board of directors, based in Washington D.C., was created. The president of this board of directors was paid much, much less than any given District Bank president; the terms of the “Directors” were shorter than those of the District Presidents; and this disproportionate compensation and term length reflected the relative power wielded by officials within the Federal Reserve System!

However, this was not the end of the evolution of the U.S. Federal Reserve!

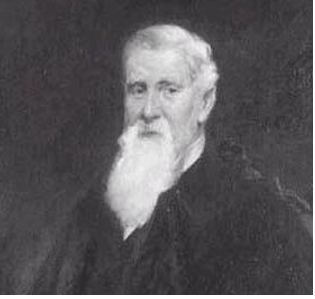

As you may have intuited from the above, “monetary policy” as we now know it was not the province of that first Federal Reserve Board of Directors. In fact, the first “open market operations were initiated by the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s President, Benjamin Strong.

This is Benjamin Strong, who as President of the New York Federal Reserve Bank initiated the very first “Open Market Operations”!

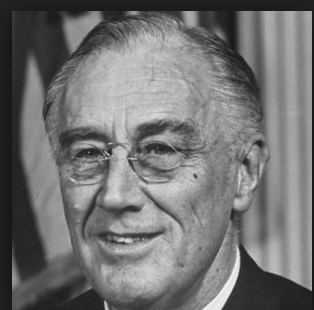

But perhaps the single most elemental event that shaped the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank into the form we know it today came in 1933, when (then first term) U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt took the nation off the the Gold Standard.

Think about that development for a moment. Along with war (which invariably ran up the federal government debt that needed to be serviced by a central bank), one of the most consistent themes in U.S. bank history were local banks that suspended “species payment”. Such suspensions angered the public and understandably led them to hold banks, and the financial system, in both contempt and suspicion.

So once Roosevelt suspended the Gold Standard in the U.S., he introduced full-fledged “fiat currency” for the first time in U.S. history (money backed strictly and completely by a “promise”, rather than an objectively and universally accepted value such as an ounce of Gold)! Therefore, a central authority was needed to zealously guard the integrity of the banking system. Recall if you will that in prior decades of U.S. history, whenever an individual bank failed to maintain discipline, or took on too much risk, or suspended its “promises” to depositors and the financial system… the nation depended upon either a national bank … or (at least between 1836 and 1863) a private bank (such as Boston’s Suffolk Bank) to intervene by bringing regulatory discipline to said bank(s), thereby restoring confidence in the financial system.

Recognizing the importance of the ongoing security and viability of the U.S. financial system, Congress determined that a formal, national financial authority was needed to marshall responsible compliance with sound national bank policy.

To accomplish this, Congress reformulated the Fed through the “Banking Act of 1935”, which involved the following:

1) Creation of a Federal Open Market Committee to regulate monetary policy;

2) Replacement of the original de-centralized structure (including the weak “Board of Directors”) with a much strengthened and more centralized structure led by a “Board of Governors”);

3) The net effect of this legislation was to reduce the independence of the 12 District Banks and bring more centralized authority to Washington, DC and the Board of Governors.

These changes were a part of an orchestrated effort to deal with the ongoing and devastating effects of the Great Depression … as well as to restore (and maintain) public trust in the financial system. It was felt that this required bank coordination and management that was more centralized in the nation’s capital – hence the “new” Federal Reserve.

I find it interesting that a central figure within the history of the Federal Reserve, Marriner Eccles, has so few images available through the Internet. This is the best one I could find!

It is because the Federal Reserve became significantly more powerful, and its leaders were granted more recognition and security, that it is not merely a point of abstract interest[17] that, in fact, the very first “Chairman” of the “Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board” was not Charles S. Hamlin (1914 to 1916), but Marriner Eccles, who led the Fed through the very difficult years of transition (from “Directors” to “Governors”) during the Great Depression. [See a list of Fed “Chairs” in the Appendix.]

The degree to which Eccles was a leader blessed with considerable financial and political acumen is evidenced by the fact that his tenure in that position is the third longest in Fed history, more than doubling the length of the tenure of William P.G. Harding (who was previously the longest tenured Fed Chair.)

READER TAKEAWAY:

So what does this fascinating history of one of the least well understood, and yet most powerful, U.S. public institutions teach us today?

1) One must wonder how no one within the current leadership at the U.S. Treasury Department remembered key elements within their secondary level U.S. History 101 classes!! Not even a 5th Grader who read an elementary-level survey text on U.S. History would be so clueless as to propose removing the image of Alexander Hamilton from the $10 bill while keeping the image of Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill!!

2) It is extremely telling (and sad) that it is entirely possible that the hit musical “Hamilton” emerged at the precisely right time to spare the nation from the illogical (and embarrassing) historical ignorance of Treasury officials by drawing public attention to the foolishness of summarily dumping one of the few recognitions offered of Hamilton’s seminal role within the financial history of the U.S.!!

3) Central banking has been a very controversial political issue for hundreds of years;

a) Hopefully you have gained some insight regarding the (long) history of opposition to a national bank within the U.S. – including the Federal Reserve.

b) You now also know the roots of accusations that it is unconstitutional.

4) A Central bank can prove to be effective as a restraining influence on national politicians who tend to believe the easiest way out of a problem is to “borrow and spend”… preferably at a low interest rate;

5) A Corollary: Unfortunately, central bankers can also be co-opted or manipulated by political leaders to keep interest rates low … in order to reduce the nation’s cost to service an escalating national debt load.

DISCLOSURE:

The author (obviously) finds the Fed and its history far too fascinating!! But at least he can take comfort in the fact that he no longer believes anything any Fed official says at any given time, nor anything any given “Fed expert” spews forth on TV… and absolutely never tries to “outguess the Fed” in his investment decisions!

Nothing in this article is intended as a recommendation to buy or sell anything. Always consult with your financial advisor regarding changes in your portfolio – either subtractions or additions.

APPENDIX:

| ERA | NAME | LONGEVITY |

| 1914-1916 | Charles Sumner Hamlin | 2 years |

| 1916-1922 | William P. G. Harding | 6 years |

| 1923-1927 | Daniel R. Crissinger | 4 years; 4 months |

| 1927-1930 | Roy A. Young | 2 years; 10 months |

| 1930-1933 | Eugene Meyer | 2 years; 8 months |

| 1933-1934 | Eugene Robert Black | 1 year; 3 months |

| 1934-1948 | Marriner S. Eccles | 13 years; 2 months |

| 1948-1951 | Thomas B. McCabe | 2 years; 11 months |

| 1951-1970 | William M. Martin | 18 years; 9 months |

| 1970-1978 | Arthur F. Burns | 8 years |

| 1978-1979 | G. William Miller | 1 year; 5 months |

| 1979-1987 | Paul A. Volcker | 8 years; 6 days |

| 1987-2006 | Alan Greenspan | 18 years; 5 months |

| 2006-2014 | Ben S. Bernanke | 8 years |

| 2014-PRESENT | Janet L. Yellen | Undetermined |

ANSWERS TO “FEDERAL RESERVE TRIVIA” QUESTIONS:

[The CORRECT answer is indicated in Bold Font]

1) In what year was the Federal Reserve legislated into existence:

a) 1935 (during the Great Depression)

b) 1921 (following World War I)

c) 1907 (due to the mid-October “Banker’s Panic”)

d) 1913 (Woodrow Wilson felt that the gold standard made currency too tight)

2) Who was officially the first Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

a) William P.G. Harding

b) Charles Sumner Hamlin

c) Marriner S. Eccles

3) Which Federal Reserve Chair holds the record for the longest term in that office?

a) Alan Greenpan

b) Paul A. Volcker

c) William M. Martin

d) Arthur F. Burns

4) Which of the following statements was that of a Federal Reserve Chair?

a) “The nation is prosperous on the whole, but how much prosperity is there in a hole?”

b) “An economist's guess is liable to be as good as anybody else’s.”

c) ”A perpetual deficit is the road to undermining any currency.” [by William McChesney Martin]

5) Which of these statements came from a Federal Reserve Chair?

a) “There is two things that can disrupt business in this country. One is War, and the other is a meeting of the Federal Reserve Bank.”

b) “People know that inflation erodes the real value of the government's debt and, therefore, that it is in the interest of the government to create some inflation.” [by Ben Bernanke in a footnote included in a 2002 speech]

c) “The whole financial structure of Wall Street seems to rise or fall on the mere fact that the Federal Reserve Bank raises or lowers the amount of interest. Any business that can't survive a one percent change must be skating on thin ice. …. But you let Wall Street have a nightmare and the whole country has to help to get them back into bed again.”

6) Which statement was actually uttered by a Federal Reserve Chair?

a) ”They don't really know what the money supply is now, even today. They print some figures — I'm not trying to make fun of it — but a lot of it is just almost superstition.” [by William M. Martin]

b) “Clearly, sustained low inflation implies less uncertainty about the future, and lower risk premiums imply higher prices of stocks and other earning assets. We can see that in the inverse relationship exhibited by price/earnings ratios and the rate of inflation in the past. But how do we know when irrational exuberancehas unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?” [by Alan Greenspan]

c) “When I started my first job [in finance]… it was an article of faith in central banking that secrecy about monetary policy decisions was the best policy: Central banks, as a rule, did not discuss these decisions, let alone their future policy intentions.” [by Janet Yellen].

7) Which U.S. President became so frustrated by the Federal Reserve that he instructed all Fed Governors to attend a mediation meeting at the White House?

a) Andrew Jackson

b) Franklin Delano Roosevelt

c) Richard Nixon

d) Harry Truman

8) Which Central Bank is oldest:

a) U.S. Federal Reserve Bank

b) Bank of Japan (“Nichigin” for short)

c) Bank of England

d) Central Bank of Russia

e) People’s Bank of China (PBC)

9) In which year was the oldest existing Central Bank founded?

a) 1990

b) 1913

c) 1948

d) 1882

e) 1694

FOOTNOTES:

[1] http://www.investopedia.com/articles/optioninvestor/09/silver-thursday-hunt-brothers.asp

[2] More precisely, The Sverigues Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

[3] We have highlighted Shiller’s work a number of times. https://www.markettamer.com/blog/could-goethe-and-schiller-have-imagined-black-monday ; https://www.markettamer.com/blog/could-goethe-and-schiller-have-imagined-black-monday-part-ii

[4] The Merton Scholes made famous by the “Black-Scholes Options Pricing Model”

[5] Markowitz and Sharpe were instrumental in developing Modern Portfolio Theory.

[6] Sharpe is most famous for his “Sharpe Ratio”, a measure of valuation; https://www.markettamer.com/blog/sharpen-your-analysis-of-ibb-xbi-and-fbt

[7] For example, I remember last October’s “V” price action… a move that most observers never saw coming and didn’t actually believe until it played out in full!

[8] This is a very polite way of saying that the lack of bank regulation often resulted in crooked bankers taking advantage of others!

[9] It is noteworthy that the New England economy and its banks suffered much less from the ill effects of the (U.S. Banking) “Panic of 1837”… in large part because of the effective leadership of Suffolk Bank – which during that Panic provided a number of “central bank like” services (eg. lending reserves to other banks and ensuring the uninterrupted operation of the payments system.

[10] I add the sobriquet “Robber Baron” to Cooke’s list of accomplishments.

[11] And unprincipled “Robber Baron”… Oh, I am sorry. He actually did have one principle: Make himself and his colleague bankers as much money as possible!

[12] Quite a number of historians suggest that J.P. Morgan played a role in creating that “Panic of 1907” (or at least pushing it to the breaking point). Once again, Morgan made a tidy profit by becoming involved in the panic’s “resolution”.

[13] in groups of ten or more, with at least $5 million in total capital.

[14] That provision sounds much more like a politician’s idea than that of a banker!

[15] Now that idea definitely came from a politician!!

[16] Rep. Glass later became involved in what we know as the Glass-Steagull Act.

[17] Or an obscure question fit for “Trivial Pursuit”

Related Posts

Also on Market Tamer…

Follow Us on Facebook

Why Sony Stock Swooned on Monday

Why Sony Stock Swooned on Monday